About

On this page

- 1. Legal Basis: Legitimate Interests vs Consent

- 2. Legal Bases

- 3. Legitimate Interests

- 3.1. Legitimate Interests Assessment

- 3.2. The Purpose Test

- 3.3. The Necessity Test

- 3.4. The Balance Test

- 3.5. Examples

- 4. Consent

- 4.1. When to Seek Consent

- 4.2. Consent for Direct Marketing

- 4.3. Consent for Cookies and Analytics

- 4.4. Examples of Consent for Other Activities

- 5. Consent vs Legitimate Interests

- 5.1. Switching Legal Bases

- 5.2. Choosing Between Consent and Legitimate Interests

Legal Basis: Legitimate Interests vs Consent

In an earlier section of the book, we discussed how important it is for processing of personal data to take place on an appropriate legal basis. We looked briefly at the legal bases provided by the GDPR.

In this section, we'll be looking in detail at two legal bases that you need to know about as a developer: consent and legitimate interests.

Legal Bases

Personal data is sacred under the GDPR. A person's personal data can, to some extent, be thought of as their property. They should be able to maintain a large amount of control over what happens to it.

But whilst personal data is an important resource, it isn't like physical property. Society is arranged in such a way that much of a person's identity and information are out in the open. Sometimes personal data needs to be shared or stored, and it isn't always appropriate or possible for a person to be asked permission for this.

For example:

- In any democratic society with an open justice system, people's names and private information will appear in court records.

- The press has a right to report people's private affairs when it's in the public interest for them to do so.

- Banks and credit institutions need to maintain records of people's finances.

The organizations listed above don't require consent in these contexts, even though they are processing highly sensitive personal data in sometimes very intrusive ways. These activities would take place under other legal bases, such as legal obligation or public task, or under an exemption.

It's important to understand that the GDPR does not impose consent as a precondition for all processing of personal data. But generally speaking, processing of personal data must take place under one of the six legal bases.

Legitimate Interests

The legal basis of legitimate interests is described by the ICO as "the most flexible of the six legal bases." This means that it is applicable in the broadest range of situations.

If you're finding that you can't really run your business, or provide your services without processing personal data in a particular way, legitimate interests may be the answer.

You often can't ask consent from your data subjects for these sorts of activities, because it might be a fundamental problem for you if they say "no."

Legitimate interests can be particularly relevant when you are not processing personal data under a contract.

However, you shouldn't think of legitimate interests as the "easy option." There's still some work to be done in determining that relying on legitimate interests is appropriate.

Legitimate Interests Assessment

When considering whether you have a legitimate interest in processing personal data in a particular way, you must conduct a Legitimate Interests Assessment.

If the data processing you want to carry out passes this assessment, you won't need to (and you most likely shouldn't) ask for your users' consent.

The ICO suggests a format for your Legitimate Interests Assessment, known as the "three-part test." You can use this test to establish whether you have a legitimate interest. This test is derived from the definition of "legitimate interests" given at Article 6 of the GDPR:

"processing is necessary for the purposes of the legitimate interests pursued by the controller or by a third party, except where such interests are overridden by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subject which require protection of personal data, in particular where the data subject is a child."

The three corresponding parts of your Legitimate Interests Assessment should therefore consider:

- The Purpose you're pursuing

- The Necessity of pursuing that purpose in this particular way

- The Balance of your interests against the privacy of your data subjects

The Purpose Test

If you think you might be able to rely on legitimate interests, here are some questions you should ask yourself about the purpose of the processing you want to carry out:

- How does the processing benefit your company or a third party?

- Do you have a clear, beneficial outcome in mind?

- Is the processing ethical and lawful?

- What would happen if you were unable to process personal data in this way?

- Are you considering any codes of conduct in your industry?

For example, under certain circumstances, engaging in direct marketing can satisfy this test. But not, for example, if you're flooding people's inboxes with spam. This would probably not be lawful, and would certainly not be ethical.

The Necessity Test

If your data processing project passes the purpose test, consider these questions about whether your processing is necessary:

- Is this processing the only viable way to achieve your purpose?

- Do you have to process personal data at all?

- Are there other ways to achieve your purposes with a much smaller data set, or a less sensitive set of personal data?

For example, let's say you want to ensure that your social networking app is not subject to abuse. This is a legitimate purpose. But asking your users to upload a scan of their passport is probably not a necessary means by which to achieve that purpose. You might not actually need to process personal data at all in order to achieve this purpose.

The Balance Test

If you believe that your data processing project passes the purpose and necessity test, you must now consider whether it strikes the right balance between your interests and those of the people whose data you're processing.

Consider the following questions:

- What is the nature of your personal data?

- Is it "special category" data?

- Would people consider the personal data private?

- Are your data subjects children?

- Would the processing be within your data subjects' reasonable expectations?

- Do you have an existing business relationship?

- How familiar are the data subjects with your company?

- Are you processing personal data in a risky or new way?

- What might the impact of this processing be?

- Will your data subjects still be able to exercise their rights over their data?

- Do you think people would be likely to object to the process if allowed?

- What safeguards have you taken to mitigate the risks or impact?

The balancing test is all about context. While you might be able to rely on legitimate interests for processing IP addresses, the same act of processing might fail if it involved payment card data.

Examples

Although the Legitimate Interests Assessment seems arduous, it is an essential part of making sure you're processing personal data in a lawful way. The chances are that you'll need to rely on legitimate interests for some element of your data processing, and you should be prepared to demonstrate that you've carried out the assessment.

We're now going to look at some examples of where web or software development companies have used legitimate interests for processing personal data.

This is a complicated area. Don't assume that these examples of legitimate interests are necessarily perfect. But none of them represent an egregious violation of the rules on legitimate interests - although it's easy to find many such examples.

We'll be considering whether legitimate interests are appropriate for these sorts of activities in the table at the end of this section.

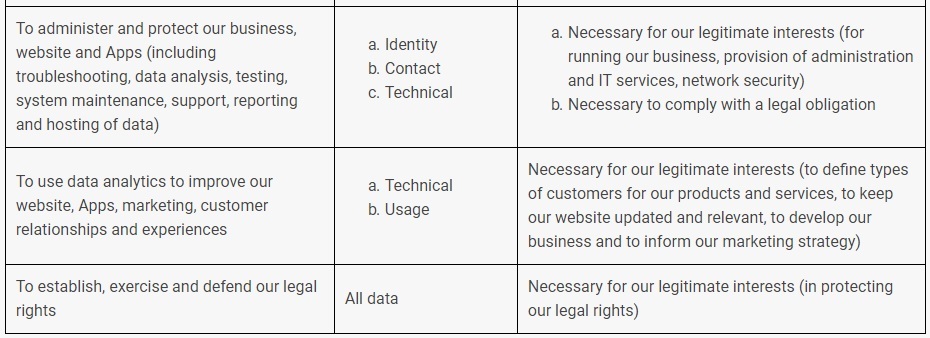

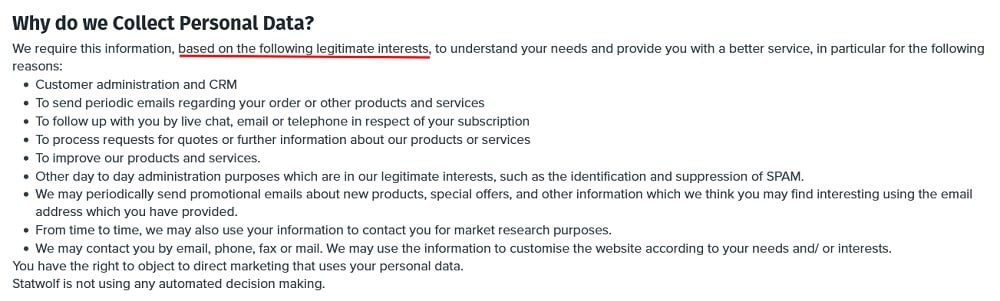

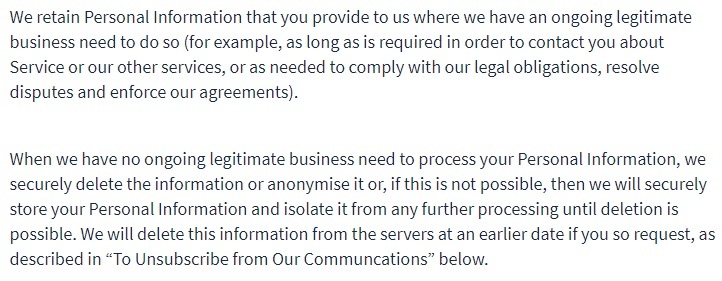

First up, here's an excerpt of a Privacy Policy that addresses the reasons why data is collected and why it's for a legitimate interest:

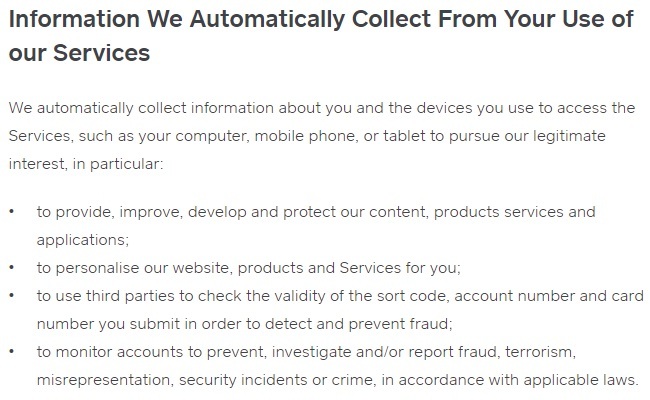

A financial SaaS company provides two Privacy Policies. One is specifically for data subjects who do not have an account. This policy lists the following activities among those for which the company relies on legitimate interests:

In its Privacy Policy for users who have an account, the company relies on legitimate interests for the following activities (amongst others):

![]()

Machine learning software company Statwolf claims a legitimate interest in the following activities:

Here's an example of an additional clause that discloses how a business relies on legitimate interests in respect of the following activities:

Consent

Consent is an extremely important concept in the GDPR. It will probably be the legal basis of choice for a lot of your data processing activity. However, many companies struggle (or neglect) to get consent in a legally valid way.

Personal data is sacred under the GDPR. As such, if you're going to request someone's permission to process their personal data, this request has to be valid and meaningful. The person must be able to say "no."

Accordingly, there's no point asking for someone's permission if they can't meaningfully refuse your request. If you have a legitimate interest in processing someone's personal data in a non-risky or intrusive way, you don't need to ask for their consent.

Equally, for processing that isn't necessary, and where you can give someone a genuine choice over how you use their personal data, you should ask for consent. But you must do so in a GDPR-compliant way.

The GDPR's high threshold of consent means that many companies fall foul of its requirements. This was evident in January 2019, when Google was fined €50 million by the French Data Protection Authority, CNIL, for violating the GDPR's conditions around consent.

We're going to look at this case, and some others, in detail in a later chapter, to help you understand how you can avoid making these mistakes with your consent request mechanisms.

For now, we won't focus on how to get consent, but when to get it. Let's consider some of the situations in which asking for consent might be necessary or appropriate.

When to Seek Consent

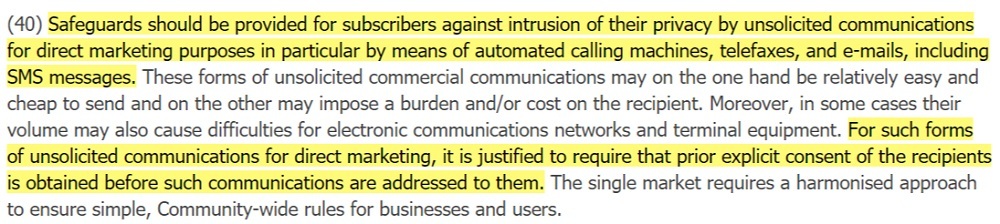

It's important to note that the GDPR isn't the only EU law that requires consent for processing personal data under certain circumstances. Another EU law known as the ePrivacy Directive (sometimes also known as the "Cookies Directive") is very important in this context.

A helpful way to think about the interaction between these two laws is:

- The ePrivacy Directive tells you what you need to get consent for

- The GDPR tells you how to get consent

Here's an excerpt from the ePrivacy Directive:

This means that you must request consent for sending unsolicited marketing communication via email, SMS, automated phone calls, and fax.

The ePrivacy Directive requires that you request consent for using certain cookies.

Let's consider these two requirements in detail.

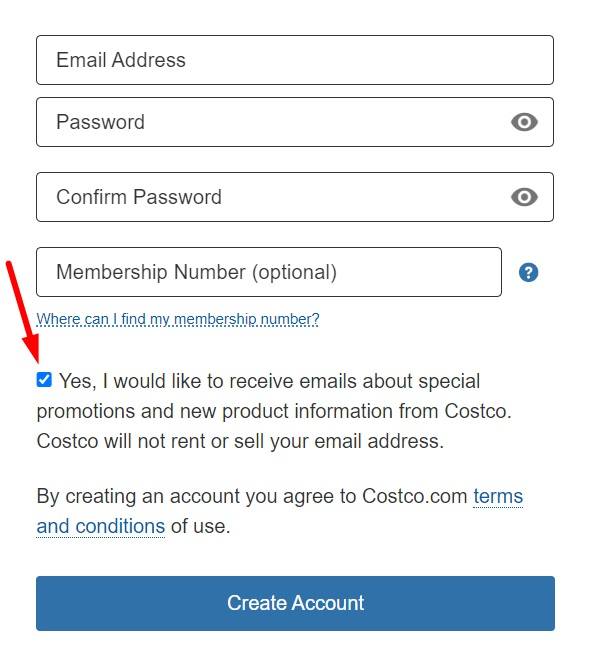

Consent for Direct Marketing

Your default way of thinking about direct marketing (i.e. marketing to a specific person, rather than the general public) should be that it requires consent.

There are certain situations where you might be able to rely on legitimate interests, even for electronic marketing, if you have a pre-existing business relationship with a customer. The ICO suggests that this might apply if:

- They have recently bought something from you,

- They provided their contact details, and

- They didn't opt out despite being given the opportunity

This is sometimes known as the "soft opt-in."

However, remember that people are quick to complain about what they perceive as spam. You must be able to justify sending every piece of direct marketing you send. The easiest way you can do this is if you have a record of the recipient having given GDPR-compliant consent.

Here's an example from Costco:

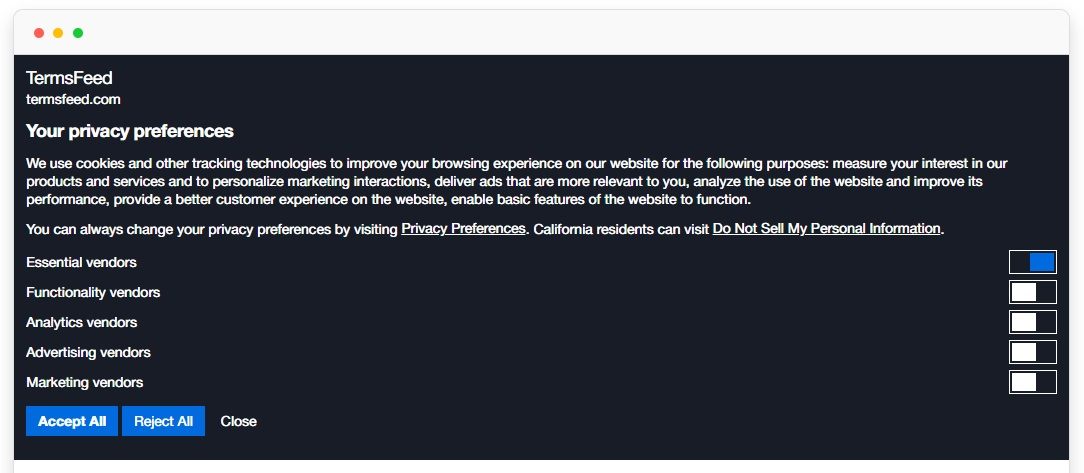

Consent for Cookies and Analytics

The ePrivacy Directive's requirements mean that you must seek consent for any cookie that is not either:

- used "for the sole purpose of carrying out the transmission of a communication over an electronic communications network"; or,

- "strictly necessary in order for the provider of an information society service explicitly requested by the subscriber or user to provide the service"

This means that you must request consent for any cookies involved in advertising - personalization, tracking, retargeting and campaign measurement.

This also has implications for analytics. The Article 29 Working Party notes that, as the law stands, even first-party analytics are not exempt from the requirement for consent under the ePrivacy Directive, despite their very low privacy risk. This is because their function is not limited to merely transmitting information, and nor is it "strictly necessary" to allow for the use of a site.

Examples of Consent for Other Activities

There's a potentially unlimited number of activities for which you might ask for consent. If you don't actually need to process personal data in a particular way, then consent might be the right legal basis for this activity.

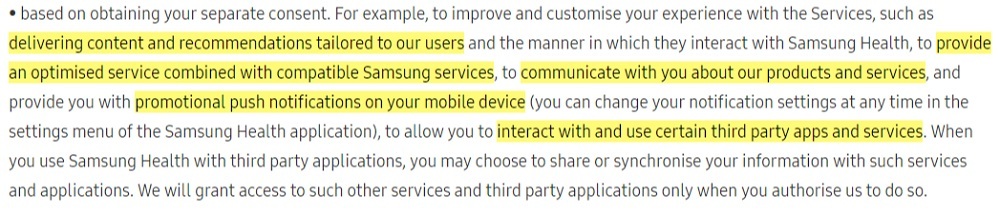

For example, here are some of the purposes for which a health app could rely on consent:

The health app notes that it seeks consent for:

- Tailoring content based on tracking user activity

- Using data to contribute to the optimization of other Samsung services

- Direct marketing

- Push notifications

- Third party app integration

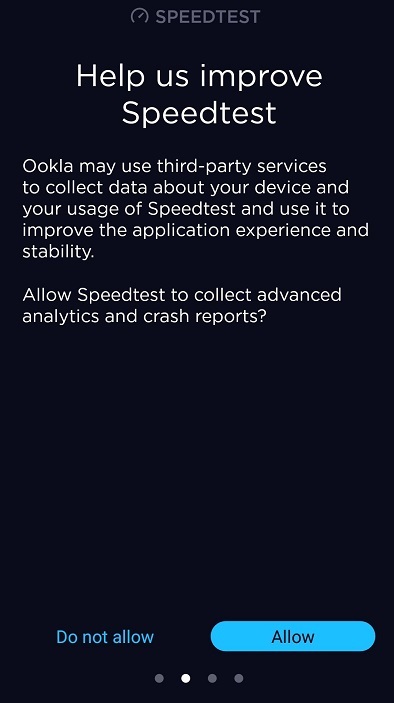

Mobile app Speedtest requests consent to send crash reports:

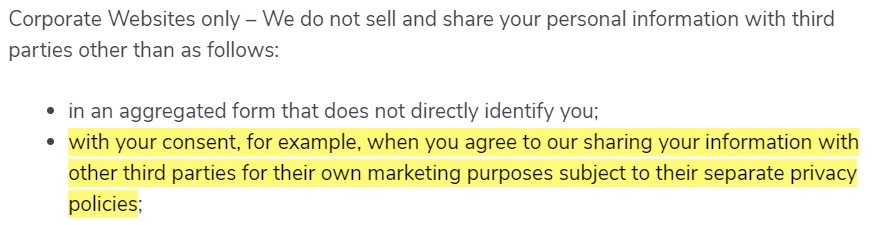

Consent can be requested for sharing personal data with third parties.

Here's how this can be explained in a Privacy Policy:

The Booking Factory seeks consent for displaying customer testimonials on its website:

Baringa seeks consent for collecting special category data:

Consent vs Legitimate Interests

Whenever your website, software or app processes personal data, you should consider whether this is necessary. If you believe it is necessary, conduct a Legitimate Interests Assessment. And try to think about this from your users' perspective. What's necessary for you to improve your business might not be necessary for your users when they use your services.

If the activity you have in mind is not necessary, or if it fails a Legitimate Interests Assessment, this doesn't mean you have to give up on the idea. You should consider whether you can seek consent instead.

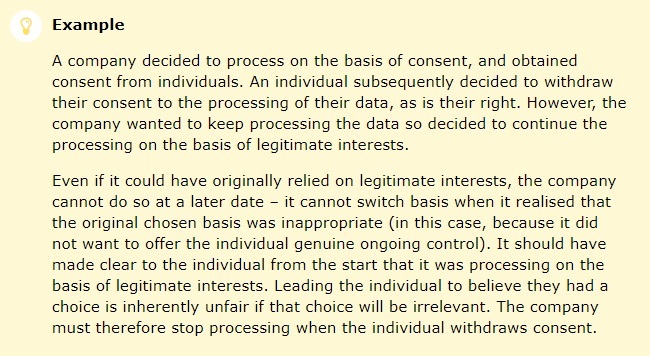

Switching Legal Bases

It's important to note that if you decide to rely on consent for a particular purpose, you can't simply argue that you have a legitimate interest for that purpose if your data subject refuses consent.

So for example, if you ask for consent for cookies, you'll have to wait until you get that consent before you set cookies on a user's device. You can't set cookies first, then ask for permission, then say it was in your legitimate interests all along if your user doesn't consent.

Here's some more information from the ICO:

Choosing Between Consent and Legitimate Interests

Here is a breakdown of the activities for which you might consider relying on consent or legitimate interest. Approach this area with caution, and remember that you can ultimately only figure this stuff out in the context of your own business.

| Activity | Legitimate Interests? | Consent? | Source |

| Maintaining network security | Maintaining network security can be a legitimate interest. This might involve logging IP addresses to detect Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks. | Consent is unlikely to be appropriate for this purpose. |

Recital 47 of the GDPR. Article 29 Working Party Opinion 06/2014. |

| Preventing fraud or abuse | Preventing fraud and misuse of services can be a legitimate interest. This might include maintaining "ban lists." | Consent is unlikely to be appropriate for this purpose. |

Recital 47 of the GDPR. Article 29 Working Party Opinion 06/2014. |

| Maintaining website or app functionality. |

If relying on legitimate to process personal data for the maintenance of your website, this must be "necessary" (from the user's perspective) for the website's functioning. You may be able to rely on legitimate interests if you anonymize certain personal data. |

It's best to rely on consent for non-essential website maintenance. For example, many websites and apps request consent for sending crash reports. |

ePrivacy Directive Article 5 (3) Article 29 Working Party Opinion 04/2012 on cookie consent |

| Using analytics | The ICO suggests that running data analytics to maintain or improve service functionality may constitute a legitimate interest, if personal data is fully anonymized beforehand. |

The Article 29 Working Party notes that both first and third-party analytics require consent. Certain providers of analytics services also require customers to earn consent from data subjects as part of the Terms of Service. |

ePrivacy Directive Article 5 (3) ICO's guidance on legitimate interests Article 29 Working Party Opinion 04/2012 on cookie consent Google Analytics Terms of Service |

| Using cookies |

You might be able to rely on legitimate interests when using certain cookies, including:

|

Third-party cookies will generally require consent. This is particularly important for behavioral advertising ("personalized" or "interest-based" advertising) cookies. It is essential to earn consent for retargeting cookies. Most retargeting providers (for example Google) require this as in the Terms of Service. Due to the ePrivacy Directive, consent is necessary even for frequency-capping and ad campaign measurement cookies. |

European Commission's guidance on cookies Article 29 Working Party Opinion 04/2012 on cookie consent ICO's guidance on cookies |

| Direct marketing |

For email or SMS, certain direct marketing might be possible under legitimate interests where there is a pre-existing business relationship with the customer; you've identified a clear benefit that cannot be achieved in other ways (e.g. indirect marketing); you're sending unintrusive and infrequent direct marketing communications. For non-automated phone calls and postal direct marketing, the rules are less strict thanks to the exemption in the ePrivacy Directive. Individuals have an absolute right to object to direct marketing. |

Any electronic direct marketing for customers with whom you do not have an existing business relationship will normally require consent. |

ePrivacy Directive Article 13 ICO's guidance on email marketing Article 29 Working Party Opinion 03/2003 on direct marketing |

| Sending administrative or transactional emails |

This is likely to be justifiable under legitimate interests if it contributes to the smooth running of your services and benefits your customer and it's not too intrusive. There should be an opt-out for non-essential transactional emails. It's also possible that a contract is an appropriate legal basis for this activity if the emails are necessary for providing your service. |

Consent would only be appropriate if these were direct marketing emails disguised as transactional emails. UK supermarket Morrison's was fined by the ICO for sending an email like this to customers who had opted out. Don't do it! |

Article 6 of the GDPR |

| Processing special category data | This is only possible under legitimate interests for certain non-profits and membership organizations. | Consent can be an appropriate solution if you need to process special category data. You must be completely transparent when seeking consent for this. |

Article 9 of the GDPR Recital 51 and 52 of the GDPR |

| Pursuing and defending legal claims |

While many companies list this as a legitimate interest, it is actually more likely to be covered by an exemption. This is a technical point, and, in reality, you're likely to be able to justify processing personal data where it's necessary to do so in the establishing, exercising or defending of legal rights. |

Consent is unlikely to be appropriate for this purpose. | ICO's guidance on exemptions |

This might sound like a frustratingly strict approach - but EU privacy law is strict. Helping you comply with this law is the purpose of this book.