About

On this page

- 1. What is the GDPR?

- 2. Why the GDPR Exists

- 3. What is Personal Data?

- 4. Territorial Scope

- 5. Principles of the GDPR

- 5.1. Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency

- 5.2. Purpose Limitation

- 5.3. Data Minimization

- 5.4. Accuracy

- 5.5. Storage Limitation

- 5.6. Integrity and Confidentiality

- 5.7. Accountability

- 6. Data Subject Rights

- 6.1. The GDPR and CalOPPA

- 6.1.1. Definition of Personal Data

- 6.1.2. Scope

- 6.1.3. Privacy Policy Requirements

- 7. The GDPR and Other Privacy Laws

- 7.1. The GDPR and the CCPA (CPRA)

- 7.1.1. Definition of Personal Information

- 7.1.2. Scope

- 7.1.3. Privacy Policy Requirements

- 8. Key Takeaways from This Chapter

What is the GDPR?

For all its insistence that businesses use "clear and plain language" when communicating with their customers, the GDPR is long, obscure and frankly bewildering in places. The GDPR can be a fantastic opportunity for developers, but only if they truly understand it.

It is possible to distill the rules and principles of the GDPR down into a comprehensible form. But a lot of misunderstandings and myths are circulating about it. Quite frankly, these misconceptions are causing people to break the law.

Before honing in on how the regulation applies to developers, we're going to get familiar with the basics.

Why the GDPR Exists

The GDPR was passed in April 2016 and took effect in May 2018. It replaced the "Data Protection Directive" which had been in place since 1995. Despite the monumental changes in the world of information technology in the two decades between the passing of the two laws, they are actually pretty similar in many respects.

The GDPR sets rules regarding the automated or semi-automated processing of personal data.

The main objectives of the GDPR are:

- To protect people's rights in relation to their personal data

- To make sure that personal data is processed in a consistent way across the whole of the EU

What is Personal Data?

The term personal data is similar to what is called personal information, or personally identifying information (PII) in other jurisdictions.

The GDPR gives a very broad definition of personal data, and it's also interpreted very broadly by institutions and courts within the EU.

Personal data is sometimes defined as information that identifies a person. This is actually too narrow a definition.

Personal data is best thought of as any information that might reveal something about a specific person.

A person's name and address are amongst the most obvious examples of personal data. On their own, a name or an address don't reveal much. But combine them, and you know where a person lives.

The principle extends to more obscure types of information.

For instance, take an IP address. This has been held by the EU Court of Justice to constitute personal data. An IP address on its own means very little. But it could, in theory, reveal a lot about a person, if linked to their name and browsing history.

Think about all the information people offer up about themselves online. Web developers and administrators can potentially handle a lot of personal data.

A notorious example is cookie data. Cookies can track users across multiple websites and monitor how they behave online.

The sort of information collected by cookies is unlikely to reveal the identity of an individual in itself. But if it were linked up with other information it could reveal a great deal about a person's personality, interests, and activities.

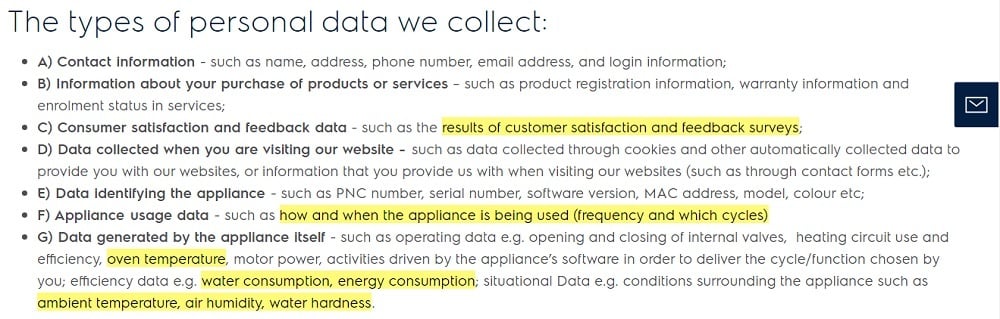

This extensive definition of personal data is particularly important given the increasing use of connected "smart home" devices.

Take a look at how Electrolux defines "personal data" in its Privacy Policy. Some of the more obscure examples are highlighted:

It may seem ridiculous at first to consider that personal data could include information about when a person's washing machine is being used, or data about a person's oven temperature and air humidity.

But given the amount of information that people are beginning to share about their private lives, isn't it sensible to treat these ostensibly banal details with sensitivity?

Territorial Scope

One of the reasons that the GDPR is such a big deal is because of its broad territorial scope, i.e. the large region it covers.

The focus is on the individuals whose personal data is being protected by the law. This means people within the EU. Or more accurately, the European Economic Area (EEA).

The GDPR law isn't restricted to citizens or even residents. Being situated within the EU at a given moment is, nominally, enough to be covered by it.

So, companies from outside the EU still need to comply with the GDPR law, so long as they're processing the personal data of people in the EU. But there are limits on this rule, and you're unlikely to fall within the scope of the GDPR "by accident."

You need to be doing at least one of the following two things in order to be subject to the GDPR:

- Offering goods and services to people in the EU, or

- Monitoring the behavior of people in the EU

Some other things could be relevant in determining whether you're subject to the GDPR:

- Whether your website or app uses a language spoken in the EU

- Whether you sell goods using an EU currency (remember that the euro is not the only EU currency)

- Whether you mention EU users in your policies or publicity

Certain things are not relevant:

- The size of your company

- Whether you are pursuing a profit

- Whether you are a charity

The GDPR also applies to a lone developer with a one-page website as much as it applies to Google. It even applies to people running a Facebook Page, due to the way that Facebook uses cookies.

Monitoring behavior has the potential to bring a large number of developers and businesses under the scope of the GDPR. It applies to behavioral advertising and the use of tracking cookies.

Principles of the GDPR

The GDPR gives a set of principles which guide all processing of personal data.

Processing personal data means collecting it, storing it, sharing it or otherwise using it in some way.

The application of these principles is, in a sense, the whole purpose of this book. If you follow them in the right way, you'll be GDPR-compliant. So, we'll be returning to each of them in detail.

Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency

The first of the principles, "lawfulness, fairness, and transparency," looks a lot like three principles in one.

Processing personal data "lawfully" means doing so in compliance with the GDPR and other laws. But it also has a more specific definition. It means only processing personal data under one of the GDPR's legal bases.

The legal bases represent a set of good, lawful reasons for processing personal data. You can't process personal data unless you have a good, lawful reason (a legal basis) for doing so.

The legal bases are:

-

Consent. You can process someone's personal data if they've given you their permission to do so. This permission must be freely given, specific, informed and unambiguous. It must be given via a clear and affirmative action, and easy to withdraw. We'll be looking at consent in detail later.

-

Contract. You can process someone's personal data if it's necessary to do so in order to fulfill or enter into a contract with them.

For example, if you ask a home insurance company for a quote, they can lawfully process personal data about you and your home.

-

Legal obligation. You can process someone's personal data if you're required to do so by law.

For example, banks are legally required to store some personal data for a long time. And employers are legally required to share their employees' personal data with tax authorities.

-

Vital interest. You can process someone's personal data if you need to do so in order to protect someone's life. This generally applies as the last resort.

For example, if someone is seriously injured and unconscious, it's legal for a doctor to access their medical records.

-

Public interest. You can process someone's personal data if you're exercising official authority, or you're performing a task in the public interest set out in law. This mostly covers public bodies or privatized industries.

-

Legitimate interest. You can process someone's personal data if it has a minimal impact on them, and you're pursuing a legitimate and ethical purpose that benefits you or a third party. We'll be looking at legitimate interests in detail later.

Lawfulness also means obeying other EU laws such as the ePrivacy Directive. This is an older privacy law that has very important rules that developers must know about regarding the use of cookies and other technologies.

Processing personal data fairly means doing so in a way that people would reasonably expect. It means not using people's personal data for unethical purposes, even if it might be technically legal to do so. It also means not deceiving people into giving up their personal data.

Transparency is a really important part of GDPR-compliance. One important step towards achieving transparency is writing a Privacy Policy.

Purpose Limitation

The second of the GDPR's principles is known as purpose limitation.

With very limited exceptions, you must only process personal data in relation to a specific purpose. You must always be clear and honest with people about your reasons for processing their personal data.

If you do need to process data for a purpose other than the one for which you originally collected it, you must go about this in the proper way. The conditions for "further processing" are addressed at Recital 50.

Here's an example of what not to do.

A travel company has a "comments" section underneath each of their blog posts. Commenting requires visitors to register with an email address for verification purposes.

A registered user leaves a comment under an article about Japan. The company then uses that person's email address to send them marketing information about Japanese vacation packages.

This is a violation of the principle of purpose limitation. The person was told that their email address was required for verification. It should not have been used for any other purpose.

Data Minimization

The principle of data minimization requires that you do not process personal data that you don't need. All the personal data you process should be relevant to your purposes.

Here's an example of how a developer might help with the fulfillment of this requirement.

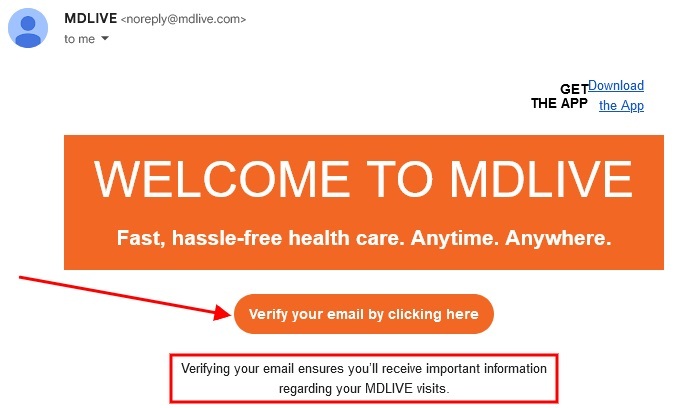

Using a double opt-in for direct email marketing is considered good practice under the GDPR. Where a person signs up to receive marketing communication, a double opt-in means sending a validation email to verify their identity.

Here's an example of how this can look:

If a person doesn't respond to this email verification email, their details should be automatically removed from a company's records within a predetermined period (say, seven days).

Accuracy

The principle of accuracy means maintaining correct and (in some cases) up-to-date records. It also means allowing people to request their personal data is rectified if they believe it to be inaccurate.

Storing inaccurate personal data can sometimes have disastrous consequences. For example, in 2012, insurance company Prudential was fined £50,000 by the UK's Data Protection Authority, the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO), after inaccurate records led to a customer's money being transferred into the wrong account.

Storage Limitation

The principle of storage limitation states that you shouldn't keep personal data for longer than you need it.

There will be some rare instances where personal data might be kept indefinitely. For example, the GDPR allows this in some cases related to research.

However, in almost every case, you must have a predetermined deletion point for each type of personal data you collect.

For example, server logs should be purged of personal data regularly (if they need to contain any in the first place), unused accounts should be deleted, and cookies should have the shortest practical lifespan.

Integrity and Confidentiality

The principle of integrity and confidentiality is sometimes called the principle of security. Developers play a crucial role in ensuring that personal data is processed securely.

Part of your fulfillment of this principle might involve certifying to a particular ISO (International Organization for Standardization) standard. This will certainly be a step in the right direction, but will not be sufficient in itself. Some of the technical and security measures discussed in this book are not covered by the ISO standards.

Part of what's required under this principle is organizational in nature: ensuring that your organization has (or, if you're a lone developer, you have) suitable procedures for identifying and dealing with security threats.

You must know what personal data is flowing throughout your systems, and you must be able to suitably restrict access to personal data records.

Accountability

The principle of accountability sits separately from the other principles in the text of the GDPR. It requires that you comply with the other GDPR principles, and that you can demonstrate your compliance.

There are many ways you can hold yourself or your organization accountable under the GDPR:

- Conducting a data audit

- Keeping accurate records

- Appointing a Data Protection Officer, if required

We will cover these issues and many more throughout this book.

Data Subject Rights

One of the ways that the GDPR achieves its aim of protecting people's personal data is by empowering them to protect it for themselves.

The data subject rights are a way for individuals to exercise control over their personal data:

- The right to be informed: Individuals must receive clear and comprehensive information about the ways in which their personal data will be processed.

- The right of access: Individuals can receive information about any of their personal data that a person or organization is processing.

- The right of rectification: Inaccurate personal data relating to an individual must be corrected at their request.

- The right to erasure (also known as the right to be forgotten): Individuals can request that their personal data is erased.

- The right to restrict processing: Individuals may restrict the ways in which their personal data is processed.

- The right to data portability: Individuals can receive a copy of their personal data so as to transfer it to another organization.

- The right to object: Individuals may object to their personal data being processed.

- Rights related to automated decision-making and profiling: Where important decisions are made by automated means, individuals have the right to human intervention.

There are many exceptions to the rights above, and some only apply where the processing takes place under particular legal bases.

We'll be looking in more detail at some of these rights and how they apply to developers in a later chapter.

The GDPR and Other Privacy Laws

The GDPR is probably the most comprehensive data protection law in the world. But it's not the only one. There are many others, including:

- The Colorado Privacy Act (CPA)

- The Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA)

- The California Online Privacy Protection Act (CalOPPA)

- The California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) and its amendments known as the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA).

- Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) in Canada

- The Enhancing Privacy Protection Act (Privacy Act) in Australia

- Several Southeast Asian countries

Let's take a look at some of the major similarities and differences between the CCPA (CPRA) and the GDPR, followed by CalOPPA.

The GDPR and the CCPA (CPRA)

Definition of Personal Information

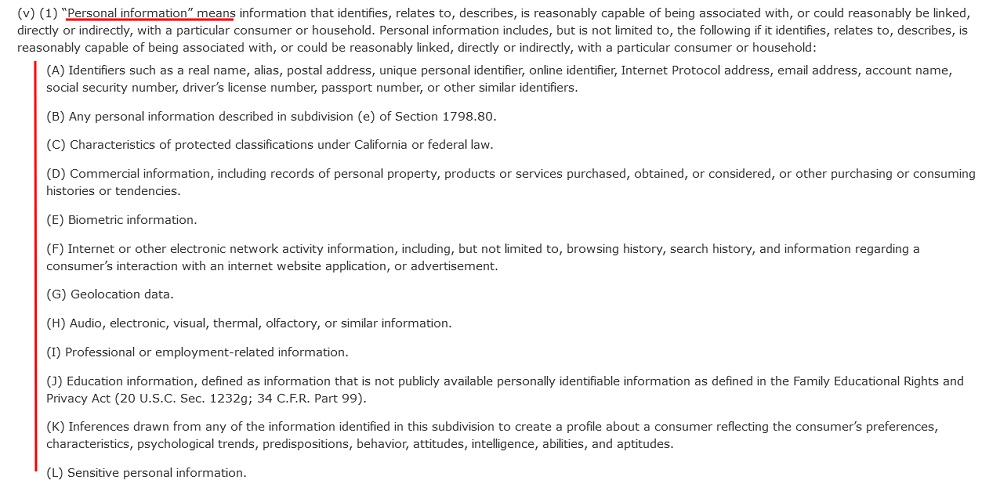

The CCPA (CPRA) defines "personal information" as the following:

"Information that identifies, relates to, describes, is reasonably capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household. Personal information includes, but is not limited to, the following if it identifies, relates to, describes, is reasonably capable of being associated with, or could be reasonably linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household."

It gives a list of specific types of information that fall under its scope:

(A) Identifiers such as a real name, alias, postal address, unique personal identifier, online identifier, Internet Protocol address, email address, account name, social security number, driver's license number, passport number, or other similar identifiers.

(B) Any personal information described in subdivision (e) of Section 1798.80.

(C) Characteristics of protected classifications under California or federal law.

(D) Commercial information, including records of personal property, products or services purchased, obtained, or considered, or other purchasing or consuming histories or tendencies.

(E) Biometric information.

(F) Internet or other electronic network activity information, including, but not limited to, browsing history, search history, and information regarding a consumer's interaction with an internet website application, or advertisement.

(G) Geolocation data.

(H) Audio, electronic, visual, thermal, olfactory, or similar information.

(I) Professional or employment-related information.

(J) Education information, defined as information that is not publicly available personally identifiable information as defined in the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (20 U.S.C. Sec. 1232g; 34 C.F.R. Part 99).

(K) Inferences drawn from any of the information identified in this subdivision to create a profile about a consumer reflecting the consumer's preferences, characteristics, psychological trends, predispositions, behavior, attitudes, intelligence, abilities, and aptitudes.

(L) Sensitive personal information

Here it is from the text of the law:

Scope

The CCPA (CPRA) will apply to a business that operates for a profit, that does business in California, and additionally meets even just one of the following requirements:

- Has a gross annual revenue of more than $25 million,

- Buys, receives or sells the personal information of at least 100,000 (100,000 or more) California residents or households, or

- Makes at least half (50% or more) of its annual revenue from sharing or selling the personal information of California residents

Privacy Policy Requirements

The CCPA (CPRA) requires a number of specific things for your Privacy Policy statement.

Your Privacy Policy must contain the following information:

- The rights granted under the CCPA (CPRA)

- A link to a "Do Not Sell My Personal Information" page

- The categories of personal information you've collected over the past 12 months

- The categories of sources where you obtain personal information

- Why you collect personal information

- How long you keep or plan to keep personal information

- The categories of personal data you've sold over the past 12 months

- The categories of personal information you've disclosed for business purposes over the past 12 months

Your Privacy Policy must be updated every 12 months to ensure it's current.

In addition, you must post a "conspicuous" link to your Privacy Policy on your website's front page (such as in the website footer).

The GDPR and CalOPPA

Definition of Personal Data

As we've seen, the GDPR's definition of "personal data" is extremely broad. In CalOPPA, the definition of personal data (which it calls "personally identifying information") is somewhat narrower.

CalOPPA lists the following as constituting personal data:

- A person's full name

- A physical address, which includes a street name and the name of a city or town

- An email address

- A phone number

- A social security number

- Any other identifier could lead to a specific individual being contacted

- Data collected by a website or app, such as cookies, but only if they are stored in a personally identifiable form alongside one the identifiers listed above

All of these examples, and much more besides (as noted earlier in this chapter), are also personal data under the GDPR.

Scope

The scope of the GDPR, meaning who and what it applies to, is also very broad, covering "automated" or "semi-automated" processing of personal data, except in the context of "purely personal or household activities."

This means that you don't have to worry about encrypting your mobile phone's contact list or anonymizing your kids' school reports. But you should assume that anything outside of the domestic context is covered.

CalOPPA only applies to:

"An operator of a commercial Web site or online service that collects personally identifiable information through the Internet about individual consumers residing in California who use or visit its commercial Web site or online service."

This includes apps, as confirmed when the California Attorney General brought a case against Delta Airlines for failing to provide a Privacy Policy with its mobile app.

CalOPPA and the GDPR apply similarly in terms of territorial scope. Both should be read as applying to businesses that are operating within, but based outside of, their respective territories.

Any commercial website that collects personal data about California residents is covered by CalOPPA. The location of the owner of that website is not a relevant consideration.

Privacy Policy Requirements

CalOPPA imposes only two obligations:

- Write a Privacy Policy, and

- Display a conspicuous link to it on your website

The GDPR imposes a huge range of obligations. One of these is to write a Privacy Policy.

Both laws also provide specific rules about what a Privacy Policy must contain. The table below broadly sets out what's required under each law.

| Privacy Policy must disclose: | GDPR | CCPA (CPRA) | CalOPPA |

| The categories of personal data processed | Yes | Yes | Yes, but specifically only personal data collected through the website or app |

| The categories of third-party recipients of the personal data | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| The existence of the data subject rights, and a method by which an individual might exercise those rights | Yes | Yes | If the commercial website operator provides a method by which users can access and make changes to their personal data, they must disclose this. Other rights do not apply |

| The process by which changes to the Privacy Policy will be communicated | This is not explicit in the GDPR, but would be good practice | No | Yes |

| The effective date of the Privacy Policy | This is not explicit in the GDPR, but would be good practice | No | Yes |

| Whether the website respects browsers' "Do Not Track" (DNT) signals | No | Yes | Yes, if users are tracked |

| Whether third parties can collect individuals' personal data over time and across other websites (e.g. via a retargeting campaign) | Yes, in that you must disclose the purposes for which personal data is processed | Yes | Yes |

| The purposes for which personal data is processed | Yes | Yes | No |

| Whether the personal data will be subject to any international transfers, and if so what safeguards will be applied | Yes | No | No |

| How long personal data is stored | Yes | Yes | No |

| Any third-party sources of personal data | Yes | Yes | No |

| Contact details of the data controller, plus its Data Protection Officer and EU Representative, if applicable. | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| The legal basis on which personal data is processed | Yes | N/A | N/A |

Keep in mind that under the GDPR, there may also be additional information required in some circumstances.

As you can see from this table, the Privacy Policy requirements under the GDPR are much more extensive than those under the CCPA (CPRA) and CalOPPA.

If you're compliant with the GDPR, you're likely to be very close to compliance with other privacy laws, too, including the CCPA (CPRA) and CalOPPA.

Key Takeaways from This Chapter

In this chapter, we've explored the basics of the GDPR, including:

- The objectives of the GDPR

- Who the GDPR applies to

- The principles of data processing

- The data subject rights

In the next chapter, we're going to look at an important concept from the GDPR, and how this applies to developers: data controllers and data processors.