Editor's Note: In July of 2023, the new EU-U.S. Data Privacy Framework was adopted.

On July 16, 2020, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) delivered its judgment on the case of Data Protection Commissioner v Facebook Ireland Ltd and Maximillian Schrems (otherwise known as "Schrems II").

The CJEU decided that the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield is no longer valid. The thousands of businesses using this scheme would be breaking the law if they continued to do so in the normal way.

The Schrems II case has the potential to severely impact trade between Europe and the United States. In this article, we'll be looking in detail at the reasoning behind the Schrems II judgment, and considering the steps that affected businesses should take following this monumental decision.

There are two main reasons why you need a Privacy Policy:

✓ Privacy Policies are legally required. A Privacy Policy is required by global privacy laws if you collect or use personal information.

✓ Consumers expect to see them: Place your Privacy Policy link in your website footer, and anywhere else where you request personal information.

Generate an up-to-date 2024 Privacy Policy for your business website and mobile app with our Privacy Policy Generator.

One of our many testimonials:

"I needed an updated Privacy Policy for my website with GDPR coming up. I didn't want to try and write one myself, so TermsFeed was really helpful. I figured it was worth the cost for me, even though I'm a small fry and don't have a big business. Thanks for making it easy."

Stephanie P. generated a Privacy Policy

- 1. Privacy Shield Overview

- 1.1. Data Protection in the EEA

- 1.2. Adequacy Decision

- 1.3. Privacy Shield

- 1.4. Schrems I

- 1.5. Downfall of Safe Harbor

- 2. Analysis of Schrems II

- 2.1. U.S. Surveillance Law

- 2.1.1. FISA 702

- 2.1.2. EO 12333

- 2.1.3. PPD-28

- 2.2. Analysis of the Schrems II Judgment

- 3. How the Schrems II Judgment Affects Businesses

- 3.1. For U.S. Privacy Shield Participants

- 3.2. For EEA Businesses Exporting Data via Privacy Shield

- 4. Summary

Privacy Shield Overview

Below is a brief explanation of the Privacy Shield framework. If you already understand the Privacy Shield framework, you can skip ahead to our analysis of the Schrems II case.

Data Protection in the EEA

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) applies all over the European Economic Area (EEA). The EEA includes the 27 European Union Member States, plus Norway, Iceland, and Lichtenstein. At the time of writing, this includes the United Kingdom (which is currently transitioning out of the EEA).

The GDPR provides a very strong level of data protection. Among many other requirements, the GDPR requires businesses to keep personal information confidential, publish a comprehensive Privacy Policy, and allow data subjects (individuals) access to their personal information.

Some other countries, including the U.S., do not have such a high level of data protection. Businesses have more freedom to sell data subjects' personal information, and the government has greater powers to intercept it.

The GDPR does not allow EEA-based data controllers to transfer personal information to third parties in those countries unless there are additional data protection safeguards in place.

Adequacy Decision

There are exceptions to the restriction on international transfers of personal information. Some countries, such as Canada, Argentina, and Japan, have data protection laws that are broadly equivalent to the GDPR.

Where a third country has a strong level of data protection law, the European Commission can make an "adequacy decision" to indicate this. EEA businesses can transfer personal information to countries with an "adequacy decision," without any special safeguards in place.

The U.S. does not have an adequacy decision.

Privacy Shield

The EU-U.S. Privacy Shield was designed to allow U.S. and EEA businesses to freely share EEA data subjects' personal information, as though the U.S. had an adequacy decision.

U.S. businesses could opt into Privacy Shield to make life easier when importing personal information from the EEA. This reduced friction when building new business relationships with EEA partners.

The Privacy Shield framework provided a set of requirements for participants. Participants were also required to certify with the framework regularly.

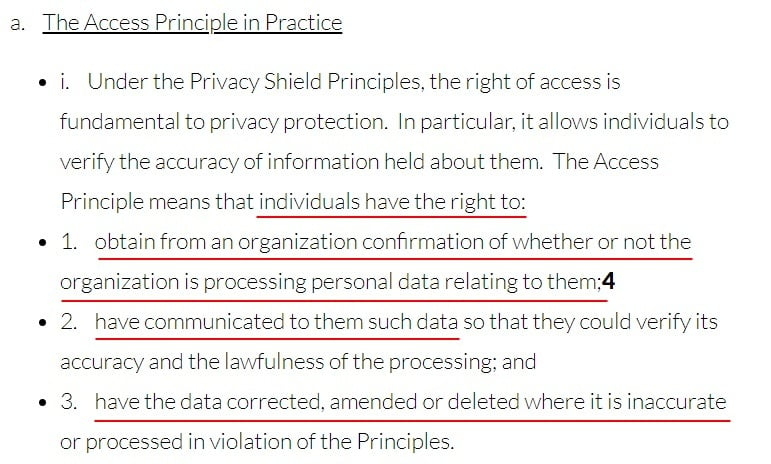

Here's an example of one of the Privacy Shield's requirements. Businesses participating in the Privacy Shield are required to grant EEA data subjects access to their personal information and correct, amend or delete their personal information if it is inaccurate:

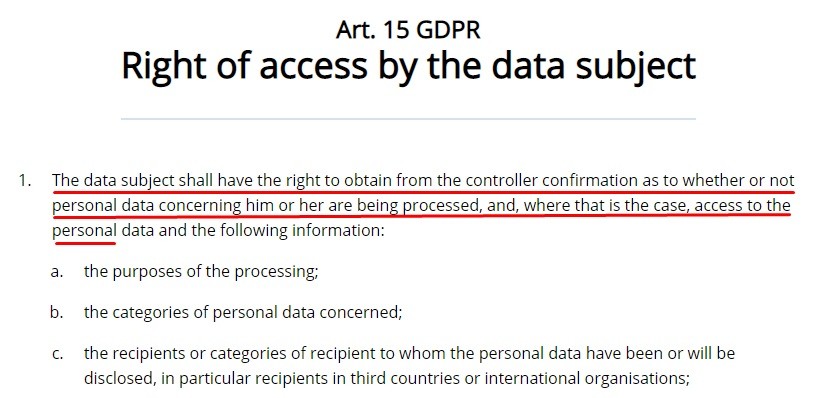

This requirement is similar to that imposed on EEA data controllers under Article 15 of the GDPR:

It also incorporates elements of Article 16:

To some extent, the above section of Privacy Shield also incorporates Article 17 of the GDPR, which allows data subjects to request the erasure of their personal information.

Other requirements under the Privacy Shield framework include:

- Implementing security measures to protect the confidentiality of personal information

- Storing personal information for no longer than necessary for a specified purpose

- Providing notice to EEA data subjects of how their personal information will be processed (e.g. via a Privacy Policy)

Schrems I

Before Schrems II there was "Schrems I" (Maximillian Schrems v Data Protection Commissioner). The first Schrems case concerned a complaint by Maximillian Schrems, privacy activist and founder of the European Centre for Digital Rights (known as "NOYB": None of Your Business).

The story of the Schrems I case began in 2013 when Edward Snowden revealed the depth of the U.S. Government's intelligence-gathering practices.

Schrems, a Facebook user, argued that Facebook was putting his privacy at risk by transferring his personal information from Facebook Ireland, based in the EEA, to Facebook Inc, based in the United States.

At the time, Facebook relied on the "Safe Harbor" framework to make these restricted transfers of personal information between its sister companies. Safe Harbor was the predecessor of Privacy Shield.

Schrems made a complaint about Facebook to the Irish Data Protection Authority, the Data Protection Commissioner. Schrems argued that the Safe Harbor framework did not protect his personal information against U.S. Government interference.

The Irish Data Protection Commissioner rejected Schrems' complaint, and, in 2015, it ended up before the CJEU.

Downfall of Safe Harbor

After considering Schrems' complaint, the CJEU declared that the Safe Harbor framework did not provide adequate personal information protection. As a result, the CJEU abolished Safe Harbor.

One key issue for the CJEU was that it did not protect personal information from the U.S. Government's access:

The CJEU also criticized Safe Harbor for:

- Not allowing EEA data subjects the opportunity to seek an effective "judicial remedy" if their rights were violated

- Not allowing EEA data subjects access to their personal information, or the opportunity to correct or delete it if it was inaccurate

The CJEU returned to some of these themes in the Schrems II judgment, as we will see below.

Analysis of Schrems II

Following the Schrems I case and the abolition of the Safe Harbor framework, Facebook began using another safeguard to facilitate its transfers of personal information to the U.S., namely Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs).

Schrems made a further complaint to the Irish DPA, arguing that, like Safe Harbor, SCCs did not protect his personal information from U.S. Government interference. Again, the Irish DPA rejected Schrems' complaint, and it ended up before the CJEU.

So, Schrems II was, centrally, not about Privacy Shield at all, but about SCCs. The CJEU concluded that SCCs are a valid safeguard for restricted transfers of personal information (with some caveats, as we will see below).

However, despite the case being about SCCs, the CJEU decided to evaluate Privacy Shield. The CJEU concluded that the Privacy Shield framework was invalid, for similar reasons that it invalidated Safe Harbor five years earlier.

U.S. Surveillance Law

Privacy Shield was invalidated partly due to its inability to protect EEA data subject's personal information from the U.S. Government's surveillance powers. Those powers are derived from national surveillance laws.

Three U.S. surveillance laws are particularly important for the Schrems II decision:

- Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA 702, available here)

- Executive Order 12333 (EO 12333, available here)

- Presidential Policy Directive 28 (PPD-28, available here)

Let's take a brief look at these three important pieces of legislation.

FISA 702

FISA 702, passed in 2008 as an amendment to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978, allows the U.S. Government to target non-U.S. citizens' communications outside of the United States.

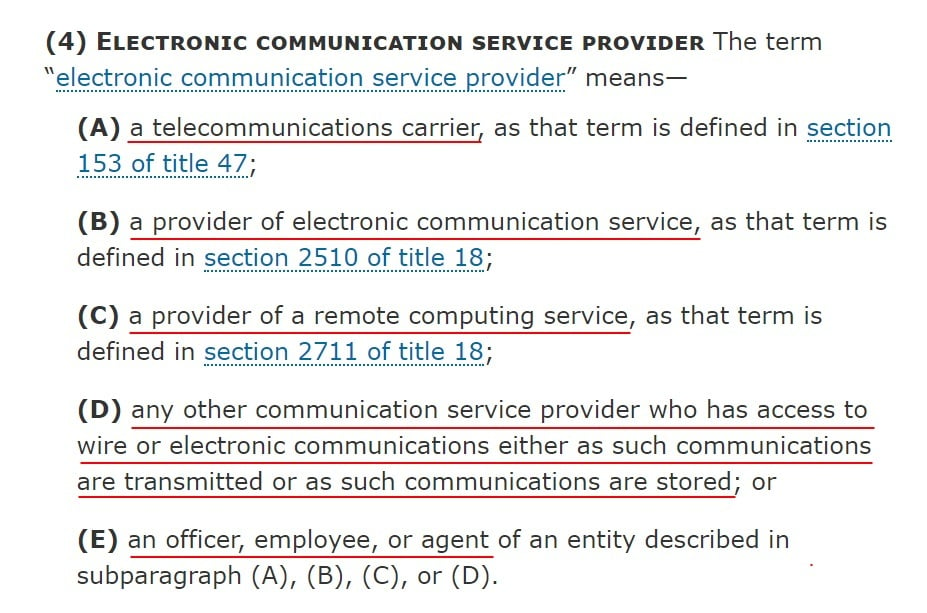

FISA 702 allows the Government to access communications without seeking a court order. It also requires certain types of companies, namely "electronic communication service providers," to assist the Government in accessing such communications.

The definition of "electronic communications service provider is given at 50 USCS § 1881 (available here):

Examples of electronic communication service providers include:

- AT&T

- Verizon

- T-Mobile

- Yahoo!

- Amazon

- Microsoft

EO 12333

EO 12333 was enacted in 1981 under President Reagan. It was amended twice under the Bush Sr administration, and once under President Obama.

EO 12333 gives the U.S. Government vast powers to collect and analyze foreign intelligence and counterintelligence. It allocates surveillance duties among Government agencies. It also forbids certain intelligence-gathering practices from taking place within the United States.

The order is considered a central piece of legislation in developing and expanding the U.S. surveillance architecture. It has been used by the National Security Agency (NSA) to justify its vast data collection exercises.

PPD-28

PPD-28 is a directive issued by President Obama in 2014, which refines and limits the ways in which the Government treats personal information collected via signals intelligence.

A key passage from PPD-28 reads:

"...all persons should be treated with dignity and respect, regardless of their nationality or wherever they might reside, and that all persons have legitimate privacy interests in the handling of their personal information. "

PPD-28 also establishes that:

- Signals intelligence should only be collected on a legitimate and lawful basis

- U.S. agencies should consider privacy and civil liberties when collecting signals intelligence

- Signals intelligence must only be collected in order to protect the national security of the U.S. and its allie

- Signals intelligence collection must be "as tailored as feasible," and there should be limits on bulk collection

Analysis of the Schrems II Judgment

Now we're going to consider the Schrems II judgment text and see why the CJEU took issue with the laws listed above.

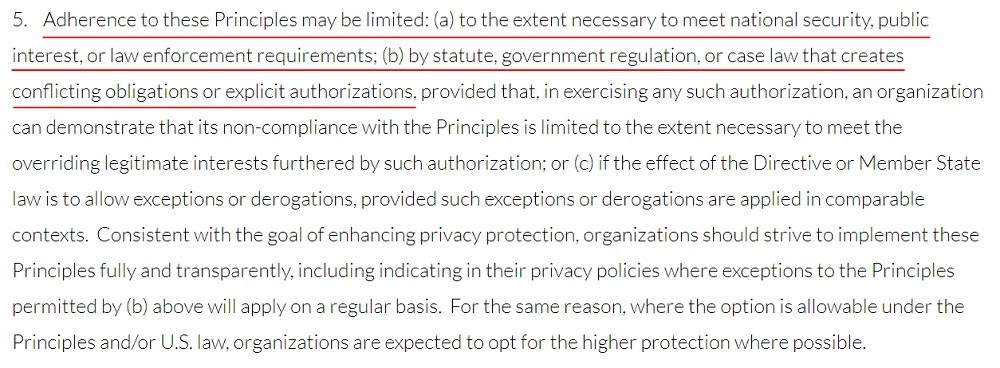

A key consideration for the CJEU was a "derogation" that appears at paragraph 1 (5) of the Privacy Shield requirements:

The provision above limits the protection Privacy Shield participants can offer EEA data subjects "to the extent necessary to meet national security" and comply with U.S. laws and regulations.

At paragraph 165 of the judgment, the CJEU considered paragraph 1 (5) and concluded that it allows U.S. public authorities to access and use EEA-originating personal information:

Access to personal information by public authorities is not, in itself, a "deal-breaker" for the EU. Surveillance is recognized as being necessary for safeguarding national security across all EU Member States. The problem is the nature of such access, as stated in paragraph 168:

There are three issues described in the paragraph above:

- Under U.S. law, public authorities can access EEA-originating personal information without the "necessary limitations and safeguards" that would make such access proportionate in the eyes of the EU

- EEA data subjects whose personal information is subject to U.S. authorities' access cannot ask a judge to review the U.S. authorities' actions.

- The Privacy Shield framework designates an ombudsperson for such purposes, but this ombudsperson does not meet the standard of a "tribunal" under the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (in other words, this is not an acceptable level of protection)

The lack of access to a judicial remedy is also considered in relation to PPD-28 (at paragraph 181):

Despite the good intentions of PPD-28 in establishing some degree of privacy when collecting signals intelligence, the directive does not go far enough to satisfy the CJEU.

Another issue for the CJEU was the fact that EO 12333 allows access to personal information based on presidential decree. The Privacy Shield framework does not effectively protect EEA data subjects against this interference (at paragraph 191):

Based on the above considerations, the CJEU concludes that the Privacy Shield is invalid (at paragraph 201):

The CJEU then considered whether the invalidation of Privacy Shield would create a "legal vacuum." This would require some sort of transition period before the use of the Privacy Shield program by EEA data controllers was rendered unlawful.

The CJEU determines that abolishing Privacy Shield would not create a legal vacuum and so it should be invalidated with immediate effect.

How the Schrems II Judgment Affects Businesses

Thousands of businesses used Privacy Shield to facilitate the import and export of data from the EEA. If you're one of these businesses, you will need to seek alternative arrangements to safeguard EEA data subjects' personal information.

For U.S. Privacy Shield Participants

The Department of Commerce (DoC) has produced a set of FAQs about the impact of the Schrems II decision, designed for U.S. Privacy Shield participants.

The key takeaways from the DoC's guidance include:

- The DoC will continue to administer Privacy Shield while working with the EU to determine what happens next.

- U.S. businesses should refer questions to the European Commission, the appropriate European Data Protection Authority, or their legal counsel.

- Businesses should continue to participate in Privacy Shield in order to demonstrate "a serious commitment to protect personal information" )note that should not be interpreted to mean that businesses should continue to transfer personal information without additional safeguards).

- Participating businesses are still required to pay their usual certification fee.

- Those businesses wishing to leave the scheme must remove all reference to Privacy Shield from their websites, Privacy Policies, and other public documents.

It is likely that SCCs will be an appropriate alternative to Privacy Shield participation for many U.S. businesses and their EEA partners.

For EEA Businesses Exporting Data via Privacy Shield

EEA businesses that export personal information to U.S. Privacy Shield participants must work quickly with their U.S.-based partners to bring about alternative arrangements.

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) has published a set of FAQs for EEA businesses. Key takeaways from the guidance include:

- Transfers made under Privacy Shield are now illegal. EEA exporters using the scheme will need to find a new way to export personal information to the United States

- There is no "grace period" throughout which transfers under the Privacy Shield scheme may continue

- Other safeguards for international transfers, such as SCCs, were not impacted by the Schrems II decision, but they may be affected by the same U.S. surveillance laws

- When making international transfers, both the exporter and the importer of personal information must assess the privacy risks involved on a case-by-case basis

It is likely that SCCs will be an appropriate alternative for many EEA businesses and their U.S. partners. For more information, see our article Using Standard Contractual Clauses.

Summary

- The EU-U.S. Privacy Shield framework served as a means to facilitate restricted international transfers of personal information from the EEA to the United States.

- In its decision on the Schrems II case, the CJEU determined that Privacy Shield did not provide adequate protection for the personal information of EEA data subjects.

-

The key reasons for the CJEU's decision were:

- The framework did not protect EEA data subjects from U.S. surveillance laws, which grant the U.S. Government a disproportionate level of access to personal information.

- The Privacy Shield Ombudsperson, designated to deal with complaints by EEA data subjects about how their personal information had been treated under the scheme, did not constitute a proper judicial remedy.

- The Schrems II decision invalidated the Privacy Shield framework on July 16, 2020, with immediate effect.

- Businesses participating in the scheme, whether as U.S. data importers or EEA data exporters, will need to implement new safeguards before continuing transfers of personal information from the EEA to the United States

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.