Senators in New York proposed a tough new consumer privacy law, the New York Privacy Act (NYPA) (NY State Senate Bill S5642). The NYPA doesn't seem likely to ever come to fruition, but it stands to show the future of privacy laws that states and countries may enact or attempt to enact.

The NYPA would have imposed extensive obligations on businesses of all sizes, forced companies to store personal data securely, and provided consumers with a formidable new set of digital rights.

If your business operates in the EU, this should sound familiar. The NYPA clearly took inspiration from the EU's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). From its definition of "personal data" to its guiding data protection principles, the NYPA would have imposed a level of data protection on businesses that would have made the EU proud.

- 1. Objectives and Scope

- 1.1. What Are the Main Aims of Each Law?

- 1.2. Who Has to Comply with Each Law?

- 1.3. What Are the Penalties for Violating Each Law?

- 2. Definitions

- 2.1. Consent

- 2.2. Consumers/Data Subjects

- 2.3. Controller and Processor

- 2.4. De-identification/Anonymization

- 3. Obligations Under the Laws

- 3.1. Data Fiduciary vs Principles of Data Processing

- 3.2. Keep Personal Data Secure

- 3.3. Comply with Consumer Rights

- 3.4. Maintain a Privacy Policy

Let's see how the two laws measure up.

Objectives and Scope

The NYPA and GDPR come out of very different legal contexts. Let's take a look at the differing aims and scope of each law.

What Are the Main Aims of Each Law?

According to the summary of the Senate bill, the NYPA would have:

- Required companies to provide information about how they de-identify personal data

- Provided new compulsory security standards for sharing personal data

- Given consumers the right to obtain information about who their personal data is shared with

- Created a new independent privacy and data protection authority

Fundamentally, the bill sought to change the nature of the relationship between consumers and the companies that process their personal data.

The GDPR was an update of a previous EU law, the Data Protection Directive. That older law already provided a very high standard of data protection across the EU. But the GDPR did introduce some important changes. For example, the GDPR:

- Introduced a new standard of consent

- Clarified the jurisdiction of the law

- Created a new system of fines and penalties

Who Has to Comply with Each Law?

Both laws are intended to apply to millions of companies around the world.

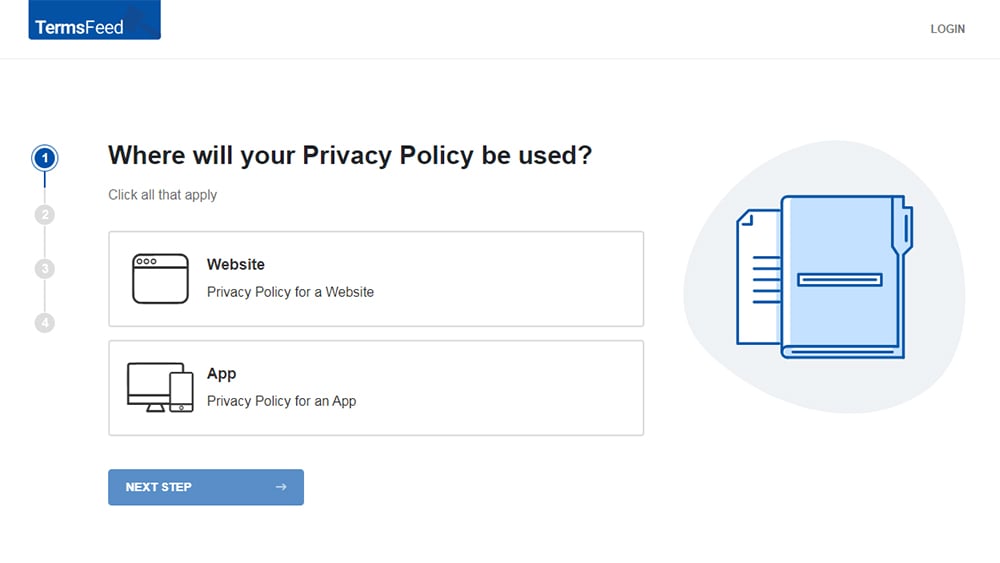

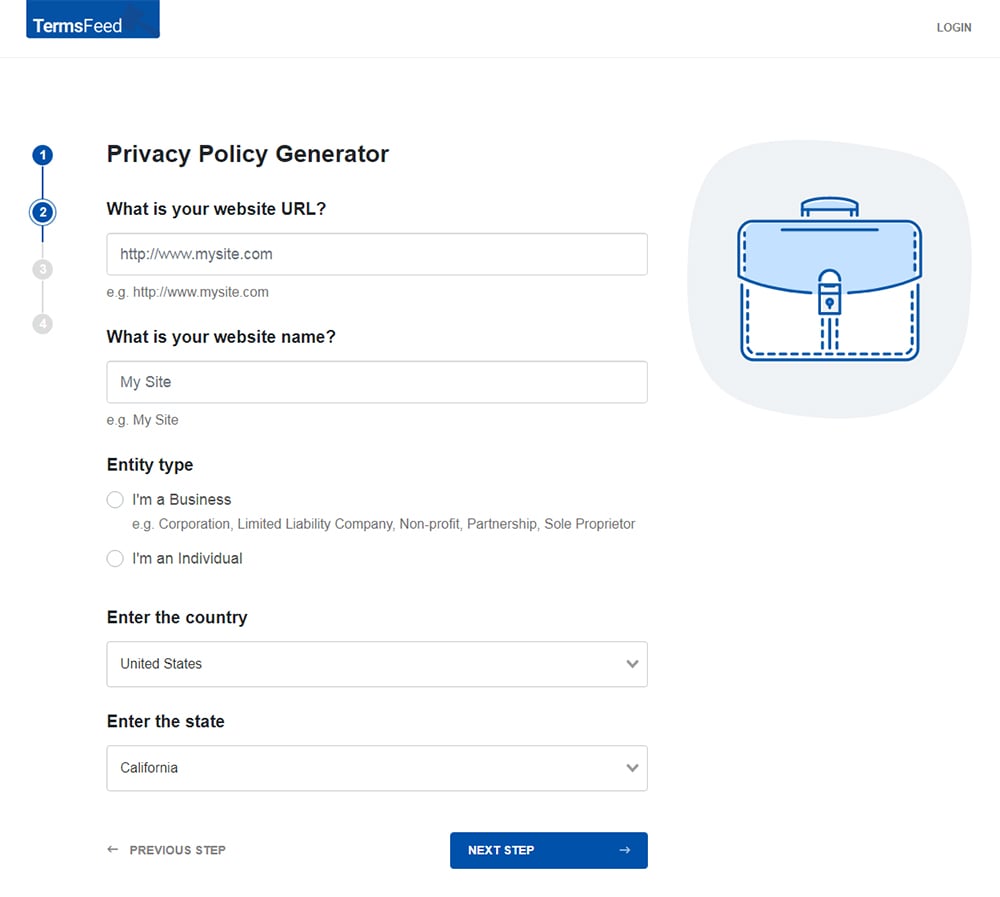

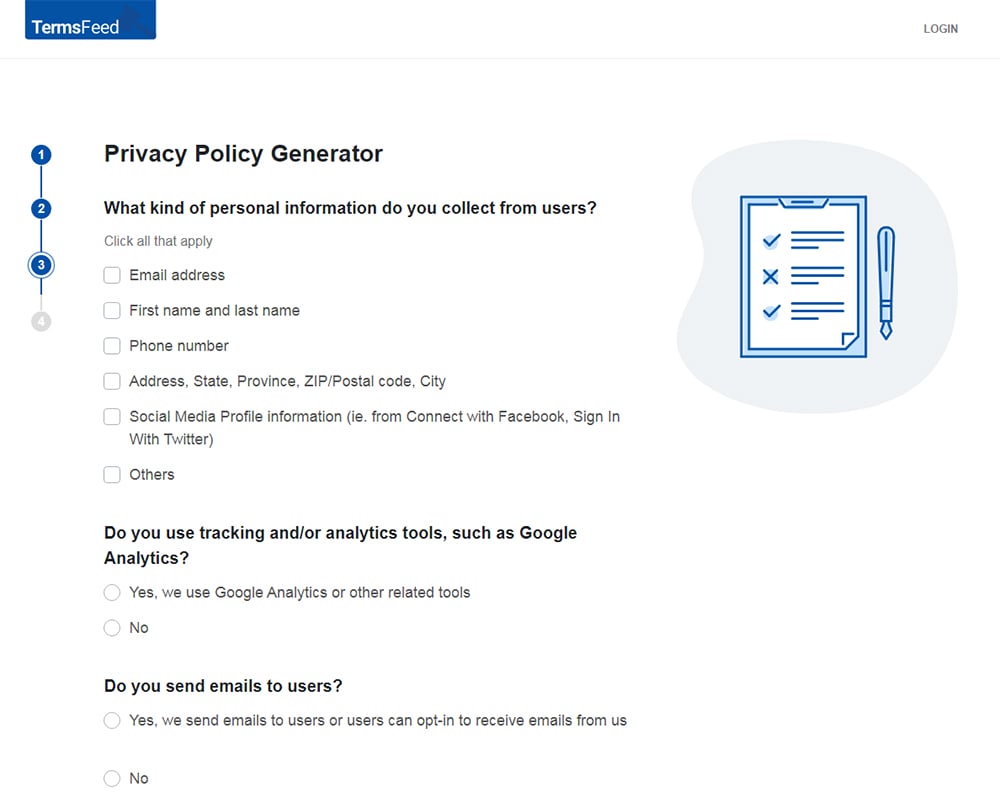

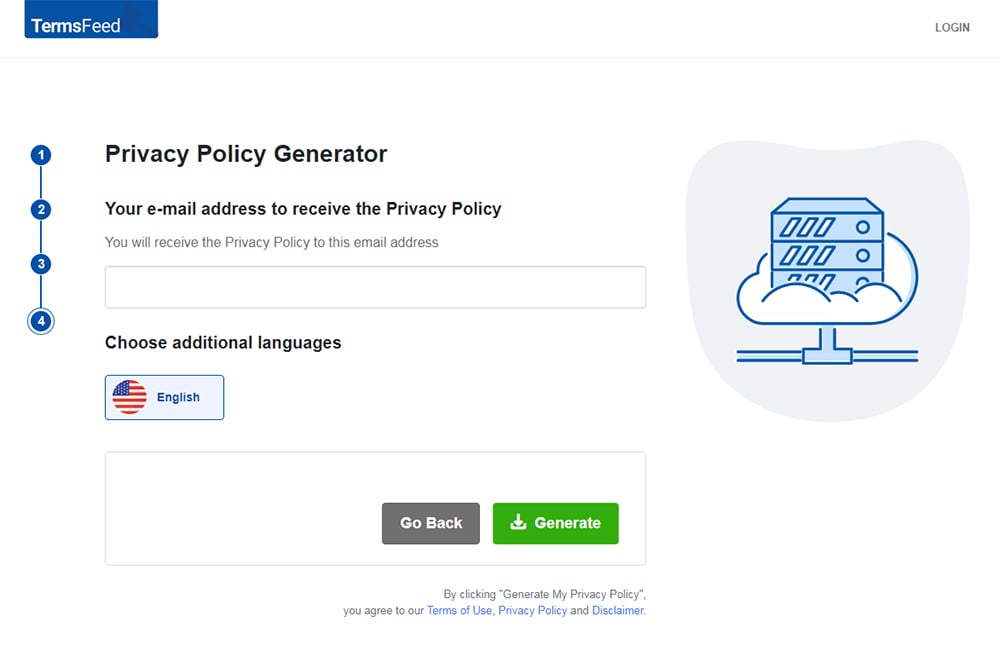

Our Privacy Policy Generator makes it easy to create a Privacy Policy for your business. Just follow these steps:

-

At Step 1, select the Website option or App option or both.

-

Answer some questions about your website or app.

-

Answer some questions about your business.

-

Enter the email address where you'd like the Privacy Policy delivered and click "Generate."

You'll be able to instantly access and download your new Privacy Policy.

The NYPA would have applied to any legal entity that:

- Conducts business in New York State

- Intentionally targets New York State consumers with its products and services

The Act was meant to apply to all organizations that are covered by the criteria above. The turnover, sector, or size of the company wouldn't have been relevant. Nonprofits and sole traders were included. However, it wouldn't have applied to state and local governments.

The GDPR applies to anyone who:

- Offers goods and services in the EU

- Monitors the behavior of people in the EU (including via targeted online ads)

Again, the size of the company is not relevant, although there are some exemptions to specific rules. Unlike the NYPA, the GDPR applies to governments as well as private companies..

What Are the Penalties for Violating Each Law?

The NYPA would have been enforced under the New York General Business Law Article 22-A: Consumer Protection From Deceptive Acts And Practices (Section 350-D). This allows civil penalties of up to $5000 per violation.

This might not sound like a lot, but a data breach involving just 1000 users could have resulted in a penalty of up to $5 million.

Violating the GDPR carries a crippling maximum penalty of up to 4 percent of annual turnover or €25 million. And the EU's Data Protection Authorities aren't afraid to use these powers. The $229 million dollar fine levied on British Airways in June 2019 is evidence of this.

Both laws also give rise to a "private right of action," meaning that private citizens can take action in court against those who have breached their privacy rights.

Definitions

The NYPA bore some striking similarity to the GDPR in how it defined certain terms. Frankly, there appeared to have been some copy-pasting going on.

Personal Data

The NYPA and the GDPR both use the term "personal data" to describe their main subject matter. This is the first sign that New York lawmakers might have been looking over the shoulders of their EU counterparts. The term "personal information" is normally used in the US.

Both laws define personal data as any information relating, directly or indirectly, to a living individual.

The NYPA provided many specific examples of personal data, including:

-

Identifiers, such as:

- Real name

- Date of birth

- Email address

-

Information such as:

- Employment history

- Credit card number

- Medical information

-

Commercial information, such as:

- Income

- Property

- Assets

-

Biometric information, such as:

- Eye scan

- Fingerprint

- Voiceprint

-

Online information, such as:

- Browsing history

- Search history

- User-generated content

All of these examples are also personal data under the GDPR.

Interestingly, however, the NYPA didn't specifically mention cookies. This matters because it would have greatly affected how businesses advertise online. It's not clear whether this omission from the NYPA's definition was intentional.

Consent

Consent is an important concept in privacy law. Certain actions, such as sharing a person's data or sending them marketing emails, are only lawful with a person's consent.

Businesses must make sure that if they're required to earn a person's consent, they ask for consent in a way that is recognized as valid under the law.

The GDPR is famous for its very high standard of consent. And that same high standard of consent was present in the NYPA.

Under both laws, consent must be:

- Affirmative

- Freely given

- Specific

- Informed

- Unambiguous

This means that under both laws:

- You can't assume you have a person's "implied" consent

- You can't earn consent via pre-ticked boxes

- You must get specific consent for specific actions, not general agreement to a set of terms

Consumers/Data Subjects

The NYPA protected "consumers." A consumer is any living individual who is a New York resident. However, this definition doesn't include individuals acting in their capacity as employees or contractors.

This exception to the definition of "consumer" means that the NYPA wouldn't protect employee records. Human resources departments weren't required to comply with the law in respect of their own company's employees.

The GDPR protects "data subjects." A data subject is any "natural person" (living individual, not a corporate entity). The GDPR does apply to employees.

Controller and Processor

The NYPA and the GDPR both regulate the activities of "controllers" and "processors." This is how the laws define people according to their relationship with personal data. Every business (or other legal entity) is a controller or a processor in some respect.

A controller "determines the purposes and means of the processing of personal data." A controller normally has an objective that can be achieved by processing a consumer's personal data. It decides how to go about achieving this goal.

For example, if Amazon wants to sell you a product, the company requires your name and contact details to do this. Amazon requests this information from you via its website. Amazon is a data controller in this context.

A processor "processes personal data on behalf of a controller." A processor normally offers its services to controllers who need to process personal data regularly. It doesn't usually have a stake in the end product of the process.

For example, Mailchimp provides an email marketing service to businesses. A company can send Mailchimp its mailing list, and Mailchimp will make contact with the company's customers on its behalf. Mailchimp is a data processor in this context.

De-identification/Anonymization

An important concept in the NYPA was "de-identified data." This means data that was once personal data but has been stripped of identifying characteristics.

The GDPR recognizes "anonymization" is a method of true de-identification. Data that is truly anonymous is not covered by the GDPR.

De-identification methods are coming under increased legal scrutiny. Businesses are collecting increasingly large amounts of data about users' online activities. Sometimes a company will claim that data is "anonymous," whereas in fact it could be linked to an individual with relatively little effort.

The NYPA defined de-identified data as:

- Data that can't be linked to an individual without using additional information that is not available to the controller.

-

Data that has been modified so much that the risk of identification is "small," as long as:

- The controller has publicly committed not to re-identify the data

- There is some "enforceable means" to prevent reidentication (this could be legal or technical in nature)

Obligations Under the Laws

Both the NYPA and the GDPR contain principles and obligations designed to protect personal data.

Data Fiduciary vs Principles of Data Processing

Under the NYPA, a company in possession of consumers' personal data would have been required to act as a "data fiduciary." This is a radical concept that would have imposed a new level of data protection responsibility on US companies.

On a fundamental level, a data fiduciary must look after a consumer's personal data. A doctor would not share their patients' data without permission, unless it was in the patient's best interests. Under the NYPA, the same principle would be extended to all businesses that control personal data.

The principles imposed on data fiduciaries are reminiscent of the six principles of data processing under the GDPR. The GDPR's six principles are more extensive than the data fiduciary obligations.

Keep Personal Data Secure

Both the GDPR and the NYPA require you to protect personal data in your possession.

The NYPA required that you:

- Keep personal data "reasonably secure" from unauthorized access

- Make regular audits of personal data and security practices

- "Promptly" inform consumers if they are subject to a data breach

The GDPR requires, among many other things, that you:

- Build security and data protection into your systems by default

- Anonymize or pseudonymize personal data wherever feasible

- Inform your Data Protection Authority and, where necessary, the data subjects within 48 hours of a data breach

Comply with Consumer Rights

Both the NYPA and the GDPR contain a set of data rights. These give consumers some control over their personal data. When a consumer wishes to exercise their rights, they simply make a request to the entity processing their personal data.

Let's take a look at how the rights under the two laws compare.

| NYPA | GDPR | |

| Right of access | Controllers must provide the following to consumers on request:

|

The GDPR incorporates all the requirements of the NYPA, and also requires controllers to provide information about:

|

| Right to rectification | A controller must correct any inaccurate personal data on request. Where appropriate they must complete an incomplete set of personal data by adding a supplementary statement. | The right to rectification is the same under the GDPR as under the NYPA. |

| Right to erasure | A controller must erase a consumer's personal data on request, unless the personal data is needed for:

|

The right to erasure is the same under the GDPR as under the NYPA. |

| Right to restrict processing | The right to restrict processing requires a controller not to process personal data in any way other than storing it. For example, the controller must remove personal data from a website but not delete it. | The right to erasure is the same under the GDPR as under the NYPA. |

| Right to data portability | The controller must provide a copy of any personal data they hold on a consumer, in an accessible, machine-readable format. | The right to data portability is the same under the GDPR as under the NYPA. |

| Right not to be subject to profiling | Controllers must not make decisions with "legal or similarly significant effects" (e.g. access to credit or housing) based solely on profiling. "Profiling" means building up a profile of a person based on their activities or personal data. | The GDPR contains a substantially similar right related to "automated decision-making". |

| Other info |

Controllers must respond within 30 days. A further 60 day extension is available where required. Consumers can exercise their rights for free, twice per calendar year. Controllers must not refuse or charge a fee for the first two requests unless they are "unfounded or excessive." |

The conditions are the same under the NYPA and the GDPR, except that there's no set restriction on the number of requests. |

The GDPR also contains two additional rights.

The "right to be informed" confers, among other things, the requirement to maintain a Privacy Policy. The NYPA also required this. We'll look at this below.

Under the "right to object," data subjects can object to the processing of their personal data in certain ways. This is most relevant to direct marketing. The right to object was not among the consumer rights in the NYPA, but consumers would have been able to object to the sale of their personal data under the NYPA.

Maintain a Privacy Policy

Both the NYPA and the GDPR require businesses to be transparent. This means maintaining a Privacy Policy that details the ways in which you process personal data.

Most businesses will already have a Privacy Policy. You need one to comply with the privacy laws of California, Australia, and Canada (to name just a few places), and to do business with many third parties like Google and Facebook.

Under the NYPA, a Privacy Policy would be required to contain information about five things:

- The types of personal data you collect

- Your purposes for using personal data and disclosing it to third parties

- Information about consumer rights

- The types of personal data you share with third parties

- The types of third parties with whom you share personal data, and their names

Many companies already provide this information in their Privacy Policies to comply with existing laws.

For example, here's how UTAM complies with point 2 above:

A GDPR Privacy Policy is, as you might have predicted, likely to be a lot longer. The GDPR requires that controllers provide, at a minimum, the following information:

- The company's name and contact details

- Names and contact details of key personnel (Data Protection Officer, EU Representative)

- Types of personal data processed

- Purposes and means of processing

- Lawful basis for processing

- Storage periods

- Categories of any third-party recipients

- Information on data subject rights

- Information about any international data transfers

Interestingly, the GDPR doesn't specifically require you to reveal the names or third parties with whom you share personal data - only the "categories" of third parties.

Here's an excerpt from the Privacy Policy of Square Enix. Note that it doesn't provide specific names for these third party recipients.

While this is fine under the GDPR, it might not have been enough information to satisfy the NYPA.

While the NYPA is likely dead in the water, it's good to understand it so you can be prepared for privacy laws of the future that will be likely to pass, and likely to be similar in scope and style to the NYPA and the GDPR.

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.