The EU and Canada see eye-to-eye on data protection. So much so that the European Commission has deemed Canada's private sector data protection standards "adequate." That might not sound like high praise. But coming from the Commission, it's quite a compliment.

However, the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Canada's Protection of Personal Information and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) are quite different laws. Whilst Canada's privacy regime has been endorsed by the EU, this doesn't mean that complying with one law guarantees compliance with the other.

Below we've answered some key questions for businesses about how these two laws compare.

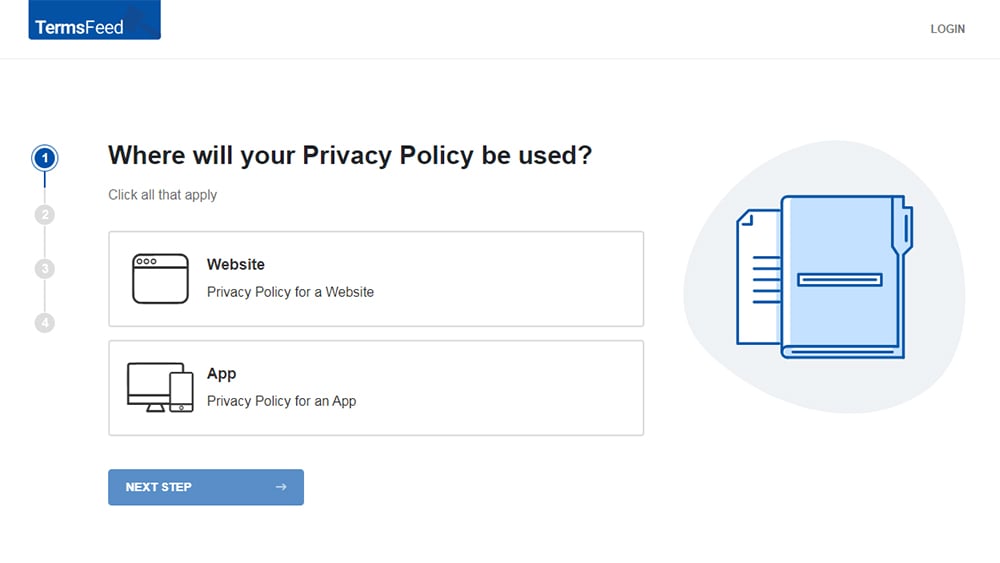

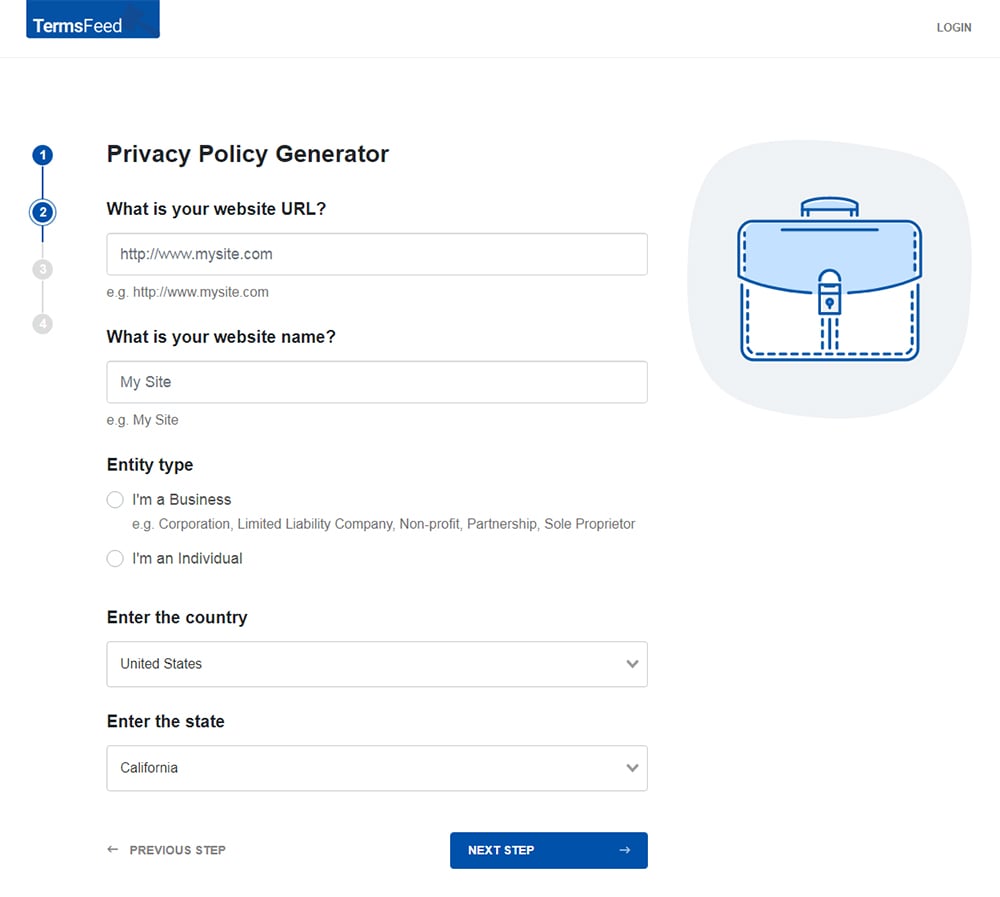

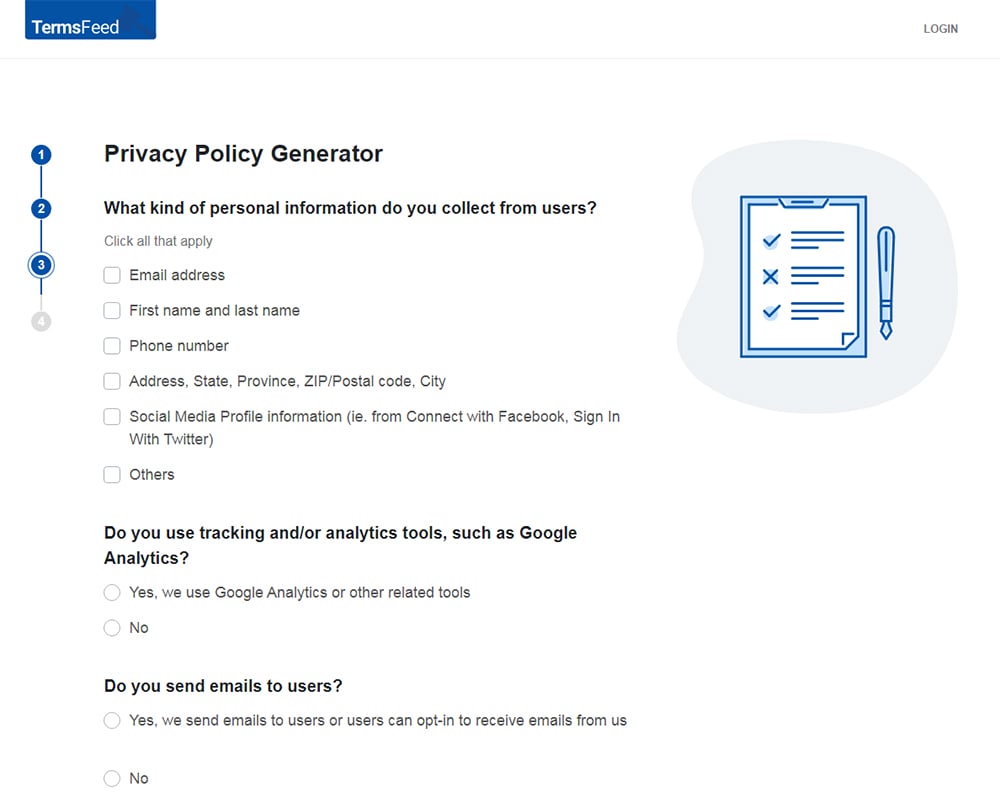

Our Privacy Policy Generator makes it easy to create a Privacy Policy for your business. Just follow these steps:

-

At Step 1, select the Website option or App option or both.

-

Answer some questions about your website or app.

-

Answer some questions about your business.

-

Enter the email address where you'd like the Privacy Policy delivered and click "Generate."

You'll be able to instantly access and download your new Privacy Policy.

- 1. How Does Each Law Define Personal Information?

- 1.1. GDPR - Personal Data

- 1.2. PIPEDA - Personal Information

- 2. Who Does Each Law Apply To?

- 2.1. GDPR - Data Controllers and Data Processors

- 2.2. PIPEDA - Private Sector Organizations

- 3. How Does Each Law Apply Across Its Jurisdiction?

- 3.1. GDPR - EU Member States

- 3.2. PIPEDA - Canadian Provinces

- 4. How Does Each Law Apply to Foreign Companies?

- 4.1. GDPR - Extraterritorial Applicability

- 4.2. PIPEDA - Jurisdiction of the OPC

- 5. How Does Consent Operate Under Each Law?

- 5.1. GDPR - Freely-Given Consent

- 5.2. PIPEDA - Meaningful Consent

- 6. What Rights Do Individuals Have Under Each Law?

- 6.1. GDPR - Data Subject Rights

- 6.2. PIPEDA - Access and Rectification

- 7. What Are the Privacy Policy Requirements Under Each Law?

- 7.1. GDPR - Transparent Information

- 7.2. PIPEDA - Openness

- 8. How Is Each Law Enforced?

- 8.1. GDPR - Data Protection Authorities

- 8.2. PIPEDA - Office of the Privacy Commissioner

- 9. Summary

How Does Each Law Define Personal Information?

Before you can apply with the GDPR or PIPEDA, it's essential that you understand what types of information each law applies to.

GDPR - Personal Data

The GDPR calls personal information "personal data." To avoid confusion we'll be using the term "personal information" when discussing both laws.

Personal information is defined at Article 4 of the GDPR, as "any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person." This can mean any information that might "directly or indirectly" identify a living individual.

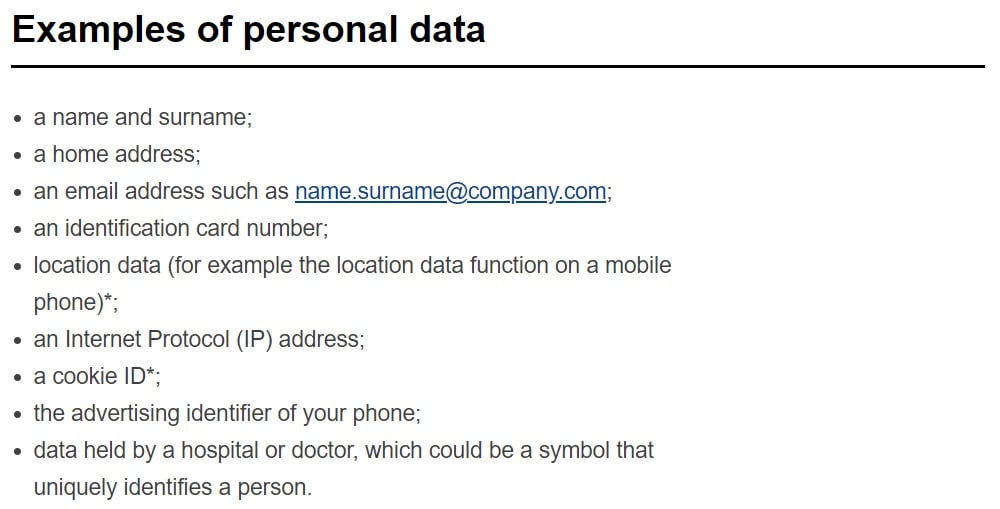

The EU applies a very broad definition of personal information. This is because increasingly sophisticated methods can be used to piece together seemingly innocuous data points to reveal a person's identity.

Here's a list of examples of personal information provided by the European Commission:

PIPEDA - Personal Information

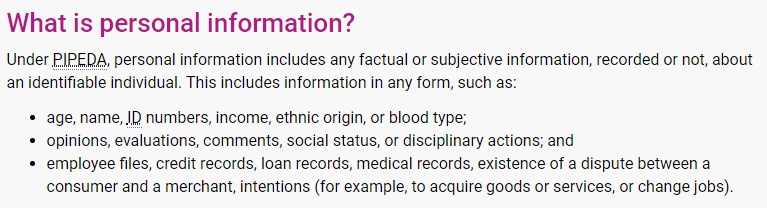

PIPEDA's definition of personal information is very similar to that of the GDPR. Personal information is defined at Section 2 (1) of PIPEDA, as "information about an identifiable individual."

Here's a list of examples from Canada's Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC):

This might seem a little more constrained than the EU's definition. But the OPC has also found that more obscure types of information, such as an IP address and cookie data, can constitute personal information.

Who Does Each Law Apply To?

Both the GDPR or PIPEDA will have a significant impact on most businesses operating in their respective jurisdictions. But neither applies to every person in every context.

GDPR - Data Controllers and Data Processors

There are two main types of organization who must comply with GDPR:

- Data controllers, who "determine the purposes and means" of the processing of personal information.

- Data processors, who process personal information "on behalf of a data controller."

Data controllers decide how and why personal information should be processed. A data controller can be anyone - a business, an individual, a government department. For example, Amazon is a data controller when it emails a customer an update on their order.

Data processors are not generally interested in the end result of the processing. Again, anyone can, in theory, be a data processor. MailChimp is a data processor when it emails a business' customers on behalf of that business. (Note that MailChimp would be the data controller in a situation where it emails its customers/businesses that it processes emails for.)

The GDPR applies across all parts of the public and private sectors, but does not cover personal information used for "purely personal or household activity."

PIPEDA - Private Sector Organizations

PIPEDA only applies to private sector organizations when they are engaged in "commercial activity." Public sector bodies are subject to another law, the Privacy Act.

PIPEDA can cover organizations who are partly government-funded (see Case Summary #2005-309) and non-profits acting in a commercial capacity (see Rodgers v Calvert).

How Does Each Law Apply Across Its Jurisdiction?

The EU is made up of separate sovereign countries. Canada consists of provinces which enjoy some degree of autonomy. This affects how each law is applied across each jurisdiction.

GDPR - EU Member States

The EU is a political and economic union made up of sovereign countries, rather than a federal state. However, the GDPR is a regulation, and so it takes legal effect directly in each EU country. Therefore, the GDPR applies whether you're in Spain, Slovakia or Sweden.

Each EU country does have a national law that implements the GDPR directly onto its statute books. The UK, for example, has the Data Protection Act 2018, and Germany has the Federal Data Protection Act (BDSG).

The differences between these national laws can be significant in specific areas. But the GDPR can be considered to apply fairly uniformly across the whole of the EU.

PIPEDA - Canadian Provinces

PIPEDA is a federal law, and so applies across the whole of Canada, except in provinces where a substantially similar private-sector data protection law exists.

In certain provinces, therefore, businesses are exempt from PIPEDA but must comply with a similar provincial law:

And the following provinces have provincial data protection law in the healthcare sector that overrides PIPEDA in this respect:

PIPEDA will always apply where businesses are transferring personal information across provincial or national borders.

How Does Each Law Apply to Foreign Companies?

Both laws attempt to regulate the activities of foreign companies. This is increasingly important as the internet continues to blur national borders.

GDPR - Extraterritorial Applicability

The GDPR applies to a company that is not established in the EU, provided that it:

- Offers goods and services in the EU, or

- Monitors the behavior of people in the EU

This could apply to any Canadian company that targets EU consumers with personalized ads or ships products to the EU.

When it comes to enforcement, any company not established in the EU is required to appoint an EU representative. This is someone who is established in the EU and can be subject to legal action in an EU-based court.

PIPEDA - Jurisdiction of the OPC

Non-Canadian businesses operating in Canada absolutely should comply with PIPEDA.

In the course of investigating a complaint against KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, the OPC stated that "foreign organizations engaged in commercial activities and that have a real and substantial connection to Canada are subject to PIPEDA."

Although the investigative remit of the OPC is clear, there is some question about whether PIPEDA's rules can be enforced against foreign entities (discussed in the case of Lawson v Accuserve).

But if you weigh up the small cost of compliance with PIPEDA against the potentially huge cost of being investigated by the OPC, non-compliance with PIPEDA is not a realistic option for any company wanting to do business in Canada.

How Does Consent Operate Under Each Law?

The key to a legally-compliant direct marketing strategy is understanding how to obtain lawful consent from customers and potential customers.

GDPR - Freely-Given Consent

The GDPR has a very strict model of consent. Six elements must be in place in order for consent to be valid.

Consent under the GDPR must be:

- Freely given

- Informed

- Specific

- Unambiguous

- Affirmative (express)

- Easily revocable

This is a high bar. It means that businesses cannot rely on pre-checked boxes or unclear sign-up forms to demonstrate that a customer has given their consent.

The GDPR also states that it will be "as easy to withdraw as to give consent." So, clear unsubscribe mechanisms are essential.

It is also possible for businesses to send direct marketing to existing customers on the lawful basis of "legitimate interests." While this is legally distinct from obtaining user consent, it is a similar mechanism to "implied consent."

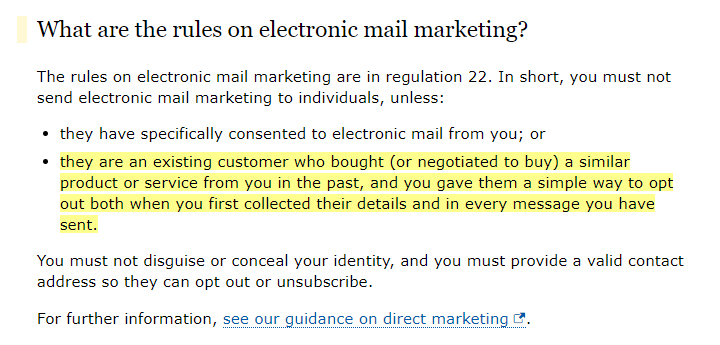

Here's how the UK's Information Commissioner's Office characterizes this rule:

This rule actually derives from another EU law called the ePrivacy Directive, but it is still valid under the GDPR.

PIPEDA - Meaningful Consent

At face value, PIPEDA's consent is less strictly defined than the GDPR's. However, it's important not to be complacent about requesting consent.

A 2015 amendment to PIPEDA added the following statement:

"consent of an individual is only valid if it is reasonable to expect that an individual to whom the organization's activities are directed would understand the nature, purpose and consequences of the collection, use or disclosure of the personal information to which they are consenting."

The OPC published Guidelines for Obtaining Meaningful Consent in January 2019. The seven guiding principles of consent suggested by the OPC create a model quite similar to the GDPR's.

Under PIPEDA, consent can be "express" or "implied." It may be possible to argue that you have a customer's implied consent for direct marketing if they are a regular customer, and your marketing correspondence is likely to be of interest to them.

However, implied consent is not appropriate if you're planning to use someone's personal information in a way that they might not reasonably expect.

Businesses must also be careful not to collect sensitive personal information without express consent (see Royal Bank of Canada v Trang).

What Rights Do Individuals Have Under Each Law?

Most data protection laws offer people some degree of access to and control over personal information. But the strength of these rights varies considerably.

GDPR - Data Subject Rights

The GDPR provides eight data subject rights.

Below is a list of these rights, accompanied by the corresponding obligations on data controllers to facilitate the rights:

- The right to be informed - Be transparent (including by maintaining a comprehensive Privacy Policy)

- The right of access - Provide an individual access to a copy of their personal information

- The right to rectification - Correct inaccurate personal information or allow user the ability to do so himself

- The right to erasure - Delete an individual's personal information

- The right to restrict processing - Temporarily stop processing someone's personal information in a specific way

- The right to data portability - Provide an individual with an organized copy of their personal data in a commonly-used electronic format

- The right to object - Stop processing an individual's personal data

- Rights related to automated decision-making - Provide human intervention if you make automated decisions with highly significant impacts

Except for number 1 (and, some argue, number 8), all of these rights are initiated by an individual's request, made directly to the data controller. Data processors are only responsible for assisting their data controllers in carrying out a request, and must not comply with an individual's request directly.

There must normally be no charge for carrying out a request, and it must normally be completed within one calendar month.

There are exceptions to most of these rights, and data controllers will not have to comply in every situation. Familiarize yourself with the specifics of each right so you can adequately provide them to your EU customers and stay compliant with an important aspect of the GDPR.

PIPEDA - Access and Rectification

PIPEDA's personal information rights are less emphatic and extensive than those granted under the GDPR.

PIPEDA provides a general right of access to personal information. PIPEDA Section 4.9 states:

"Upon request, an individual shall be informed of the existence, use, and disclosure of his or her personal information and shall be given access to that information."

Section 4.9 also provides a right to rectification similar to that under the GDPR:

"An individual shall be able to challenge the accuracy and completeness of the information and have it amended as appropriate."

There is also a very limited right to erasure, although this is far narrower than the equivalent right under the GDPR (which is sometimes known as the "right to be forgotten"):

"Depending upon the nature of the information challenged, amendment involves the correction, deletion, or addition of information."

A business should not normally charge for carrying out a request. However, it can charge a small fee if an estimate is provided to the individual beforehand.

A business must normally comply within 30 days.

What Are the Privacy Policy Requirements Under Each Law?

Privacy Policies give individuals up-front information about an organization's privacy practices. They are essential to compliance with a fundamental obligation of transparency.

GDPR - Transparent Information

The GDPR's transparency requirements are extensive, and a GDPR-compliant Privacy Policy should cover virtually all information about how a data controller processes personal information.

This includes:

- The identity and contact details of the data controller

- The types of personal information that the company processes

- The purposes and means of the processing

- The lawful basis for processing each type of personal information (such as consent)

- How long personal information is stored

- The types of organizations (third parties) with whom personal information might be shared

- Information about how consumers can exercise data subject rights and how they can make a complaint

- Details of any international transfers of personal information or automated decision-making

Privacy Policies must be accessible, particularly at the point at which personal information is collected, and written in clear and plain language.

PIPEDA - Openness

"Openness" is an important principle in PIPEDA. Under the principle of openness, businesses are obliged to make the following information available:

- Contact details of the company

- Details about the right of access

- Types of personal information stored

- How personal information is used

- A copy of any relevant company policies

- Details of any personal information shared with "related organizations"

A person should be able to obtain this information "without unreasonable effort," such as through a PIPEDA-compliant Privacy Policy.

How Is Each Law Enforced?

Data protection laws require "teeth" and legally binding rules in order to be effective. This usually means a combination of investigative powers, warnings, and financial penalties.

GDPR - Data Protection Authorities

Each EU country has a Data Protection Authority (DPA) that enforces the GDPR. These independent public authorities have a process for working together across national borders.

DPAs are independent public bodies with three broad types of powers:

- Investigative powers - To demand information, conduct audits, and enter premises

- Corrective powers - To provide warnings, give orders, and issue fines

- Advisory powers - To advise lawmakers, authorize projects, and approve standards

Fines under the GDPR can be very severe. At worst, they can reach €20 million, or 4 percent of a company's annual turnover (whichever is higher).

The French Data Protection Authority issued Google with a fine of €50 million in January 2019 in relation to its practices around consent.

Individuals can also bring a civil legal claim against a company that has violated their data protection rights.

PIPEDA - Office of the Privacy Commissioner

The Office of the Privacy Commissioner (OPC) is the independent public authority responsible for investigating complaints made under PIPEDA.

The OPC's powers are largely investigatory, meaning that it can demand information and conduct audits.

The only monetary penalties specifically set out explicitly in PIPEDA are for failing to comply with an investigation of the OPC into a data breach. This can lead to fines of up to $10,000 or $100,000 depending on the offense.

Some provinces have separate commissioners: the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for Alberta and the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner for British Columbia.

Summary

We've covered many of the differences between the GPDR and PIPEDA. It should be clear to you that the GDPR is more comprehensive and demanding. But principles of transparency and accountability pervade both laws.

There are many similarities. Both the GDPR and PIPEDA:

- Are enforced by independent public bodies

- Define personal information very broadly

- Apply to foreign companies

- Require a Privacy Policy of some sort

There are also many differences. For example:

- The GDPR makes provision for much more severe penalties.

- The GDPR applies to all organizations. PIPEDA only applies in the private sector.

- The GDPR only recognizes express consent. PIPEDA recognizes both express and implied consent.

- The GDPR provides eight rights over personal data. PIPEDA arguably provides only three.

- The GDPR applies across the whole of the EU. PIPEDA doesn't apply in every province of Canada.

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.