Privacy law evolved to protect citizens against state surveillance. But it increasingly focuses on protecting citizens from online surveillance by international businesses.

The internet's porous borders have forced lawmakers to extend the jurisdiction of national privacy laws. Increasingly, such laws now apply both to domestic and foreign businesses.

We're going to look at how privacy laws in the EU and two important U.S. states (California and New York) apply to businesses based outside of those jurisdictions.

TermsFeed is the world's leading generator of legal agreements for websites and apps. With TermsFeed, you can generate:

European Union Privacy Laws

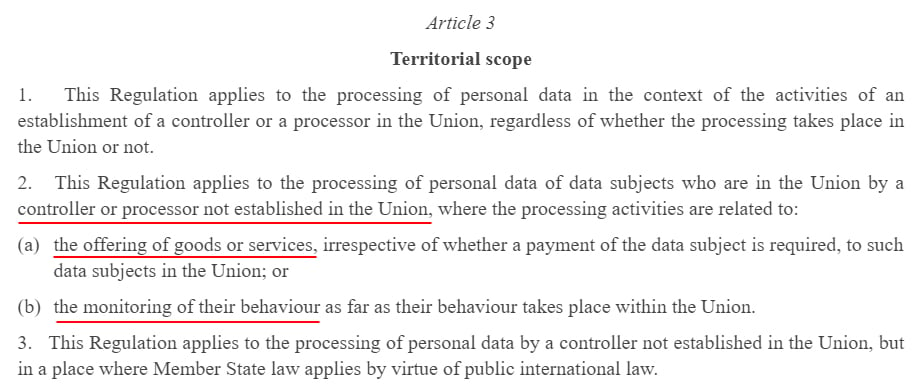

The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was, arguably, the first privacy law to explicitly state that it applied to people situated outside of its geographic jurisdiction (sometimes called "extraterritorial application"). It does so at Article 3:

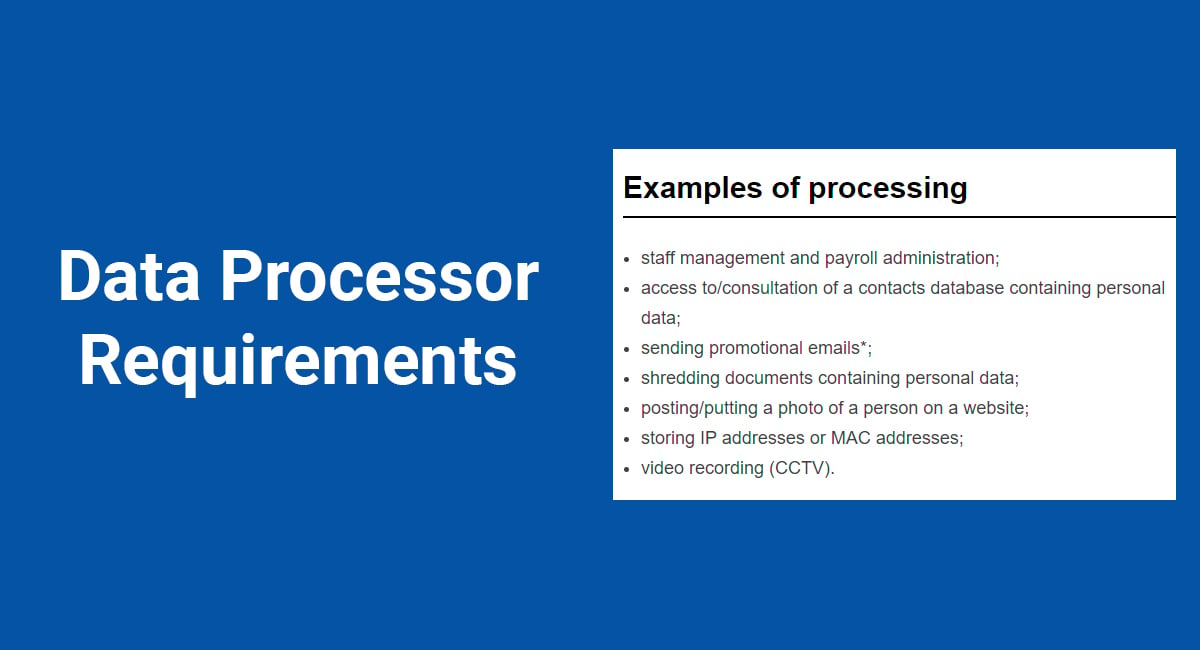

As you can see, there are three ways in which the GDPR asserts its jurisdiction over controllers and processors (we'll use the term "businesses" henceforth, but any person or organization can be a controller or processor):

- If the business is established in the EU

-

If the business is established outside of the EU, but it:

- Offers goods or services in the EU, or

- Monitors the behavior of people in the EU

- If the business is established outside the EU but is operating in a place where the law of an EU country applies

We're going to focus on the first two points.

Businesses Established in the EU

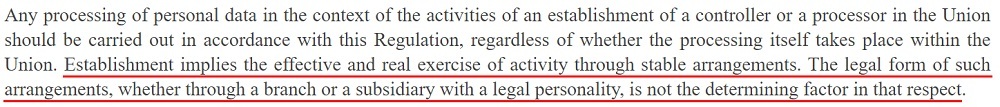

Recital 22 offers some help in determining whether a business is "established in the EU":

Further insight comes from the European Data Protection Board (EPDB) at page 5:

There's also some case law on the establishment of businesses in the EU. Here's an example, from case C-213/14, Weltimmo v NAIH, at paragraph 30:

We can draw a few conclusions from these authorities:

- A business does not need to have a branch or subsidiary in the EU for it to be established in the EU

- The main factor in determining whether a business is established in the EU is whether it has "stable arrangements" in the EU

- Whether or not a business has "stable arrangements" in the EU is specific to the nature of that business

- Where a business offers goods or services exclusively online, the threshold is particularly low

- The presence of just one "employee or agent" of the business in the EU might be enough to constitute "stable arrangements" (and thus imply that the business is established in the EU)

- A business may also be established in the EU if it maintains the equipment necessary to deliver its services in the EU

From the principles described above, we can conclude that a business is likely to be considered "established in the EU" if it has one or more employee or agent located in the EU (it is not clear whether this would include a contractor), particularly if it operates mostly online.

Businesses Not Established in the EU

Whether or not your business is established in the EU is, for the most part, immaterial insofar as it affects your GDPR compliance operations.

However, it's important to dispose of one common misconception about the GDPR. When a non-EU business processes the personal information of an EU resident, it isn't automatically subject to the GDPR. The business must also be "targeting" people in the EU.

Here's how the EDPB puts it (at page 14):

So, if your business is not established in the EU, you'll still need to comply with the GDPR if you are:

- Offering goods or services to people in the EU, or

- Monitoring the behavior of people in the EU

Offering Goods or Services

Recital 23 offers some further detail about "offering goods or services":

From this, we can conclude the following about the "offering goods or services" rule:

- The goods or services may require payment or be available for free

- A business only needs to "envisage" offering goods or services in the EU

-

When deciding whether a business offers goods or services in the EU, circumstantial evidence can be considered, such as:

- The business uses a language spoken in the EU

- The business uses an EU currency

- The business makes reference to EU users, e.g. on its website

- The mere accessibility of a business's website in the EU does not meet the threshold on its own

The EPDB considers the following factors to be also relevant in determining whether a business is "offering goods or services" in the EU:

- The business pays a search engine for a digital referencing service in order to facilitate EU users' access to its website

- The business has ad campaigns targeting EU consumers

- The business offers international services, such as tourism services

- The business has dedicated EU-user contact details

- The business uses a top-level domain associated with an EU country, such as .pl or .ie

- The business provides travel instructions to its premises from an EU country

- The business displays testimonials from EU users on its website

There shouldn't really be any ambiguity about whether your business offers goods or services in the EU. If you want EU customers, you'll have to process their personal information in accordance with GDPR.

Monitoring Behavior

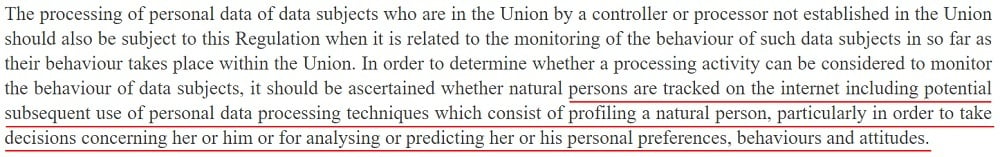

Recital 24 offers some further details about the "monitoring of behavior." This provision is a little less clear cut than the "offering goods or services" rule.

Recital 24 refers to persons being "tracked on the internet," and the use of their data for "profiling," in order to make decisions about them, or to analyse or predict their preferences. Here, the GDPR asserts jurisdiction over behavioral advertising campaigns.

But consider this light of the fact that the "mere accessibility" of a business's website from within the EU doesn't bring that business within the scope of the GDPR.

So, what if your website is "merely accessible" within the EU, you have no intention of offering goods or services to EU consumers, but EU visitors to your website will get "caught up" in your personalized advertising campaign?

The EDPB states that it "does not consider that any online collection or analysis of personal data of individuals in the EU would automatically count as 'monitoring'." However, it does list behavioral advertising among the types of activities that would normally constitute monitoring.

The upshot of this is that, if you are a non-EU business that runs personalized ad campaigns (using cookies or similar technologies), you will need to comply with the GDPR in respect of EU users who might be subject to these campaigns.

This means you must not set tracking cookies on the device of any user whose IP address originates from an EU country unless you have their explicit, opt-in consent.

Along with behavioral advertising, the EDPB provides the following examples of activities that might constitute "monitoring":

- Geo-localization

- Fingerprinting (a type of online tracking)

- Personalized diet and health analytics

- CCTV

- Market research based on individual behavioral data

- Monitoring individual's health status

United States Privacy Laws

Next, we're going to look at how "extraterritorial application" works in two U.S. privacy laws: the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) as amended by the CPRA, and the New York SHIELD Act.

California Consumer Privacy Act

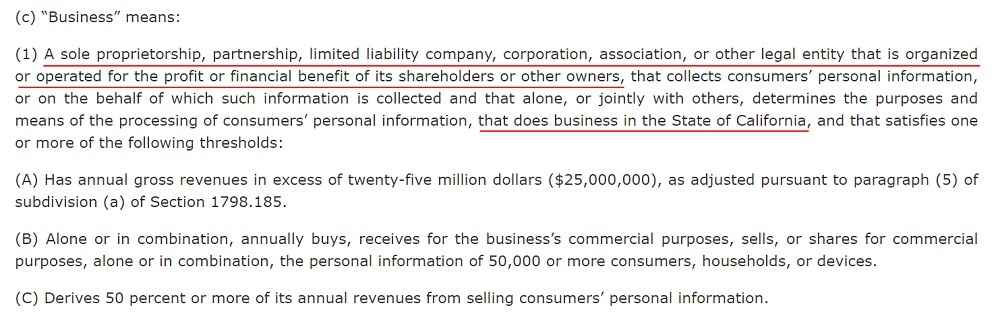

The CCPA (CPRA) applies to companies that "do business" in California. Here's the relevant part of the CCPA, Section 1798.140 (c)(1):

This appears to impose a similarly broad territorial remit as the GDPR. But because of the more limited way the CCPA (CPRA) applies, its scope is somewhat narrower:

- The CCPA (CPRA) only applies to "legal entities" operating "for profit" (i.e. private businesses)

- The CCPA (CPRA) only applies to businesses that meet one or more of its "three thresholds" (see our article Are You a Business or a Service Provider Under the CCPA?)

- A business must also "determine the purposes and means of the processing of personal information," meaning that it decides why and how to process personal information

Whether a company is established in California is irrelevant to whether it "does business" in California, and there is no need to consider the factors set out in the GDPR, such as "stable arrangements."

The CCPA/CPRA's Section 1798.140 (c) (1) (B) serves a similar function to the GDPR's Article 3 (2)(b), in that it (arguably) extends the scope of the CCPA (CPRA) to companies that collect the personal information of California consumers for the purposes of behavioral advertising.

Above, we explained how the GDPR's scope extends to non-EU businesses "monitoring the behavior" of EU residents, and that this includes businesses engaged in personalized advertising campaigns.

The CCPA (CPRA) applies to non-California businesses that sell or share the personal information of at least 100,000 California consumers per year. It's becoming increasingly clear that this includes sharing cookie data with third-party advertising providers such as Google and Facebook.

For more information, see our article CCPA: Does Using Third-Party Cookies Count as Selling Personal Information?

New York Shield Act

Another important U.S. privacy law that asserts a broad territorial scope is the NY SHIELD Act.

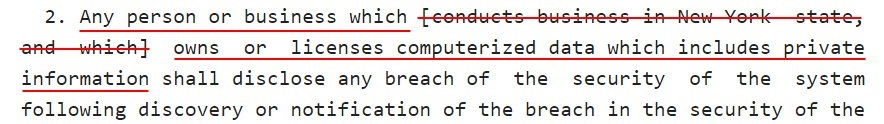

One difference between the CCPA and the NY SHIELD Act is that the "doing business" phrase was actually removed during the drafting of the New York statute:

As you can see, the NY SHIELD Act applies to "any person or business who owns or licenses" computerized private information (defined as certain categories of the personal information of New York residents). "Doing business" in New York is not a relevant consideration.

This clearly signals the New York Senate's desire to extend the territoriality of the Act as far as possible. But what substantive difference might the omission of the "doing business" rule have on the application of the Act?

Ultimately, the difference in interpretation can only be decided by the courts. However, the application of the SHIELD Act would appear to be broader than either the CCPA or the GDPR.

- The CCPA only applies to businesses engaged in commercial activity

-

The GDPR only applies if a person or business processes an EU resident's personal information and:

- It is established in the EU, or

- It offers goods or services to people in the EU, or

- It monitors the behavior of people in the EU

Bear in mind, though, that the definition of "private information" is much narrower than "personal information" under the CCPA (CPRA) or "personal data" under the GDPR. An example of private information is a credit card number stored alongside an unencrypted security code.

Therefore, it is unlikely that a person or business would "own or license" the private information of New York residents without also "doing business" in New York.

For all intents and purposes, the NY SHIELD Act applies extraterritorially in much the same way as the other two laws we have considered.

Summary

We've looked at how three important privacy laws apply to businesses based outside of their geographical territories.

-

The GDPR applies to a person or business that processes an EU resident's personal information, and:

- Is established in the EU, or

- Offers goods or services to people in the EU, or

- Monitors the behavior of people in the EU

- The CCPA (CPRA) applies to any business that operates for profit, meets its threshold requirements, and "does business" in California

- The NY SHIELD Act applies to any person or business who owns or licenses computerized private information (that is associated with New York residents)

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.