The United States, unlike many other legal jurisdictions, has no general privacy or data protection law. At the federal level, CAN-SPAM regulates commercial email, COPPA covers websites and apps aimed at children, and the Federal Trade Commission provides some best practice guidance.

The state of California has long been at the forefront of regulating online privacy in the United States. Since 2004, website admins and businesses have been creating Privacy Policies to comply with the California Online Privacy Protection Act (CalOPPA). California's privacy law, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), passed in June 2018, and took effect on Jan 1, 2020.

It was amended and expanded even further by the CPRA, which took effect on January 1, 2023.

The laws are very different. Compliance with CalOPPA looks relatively easy compared to the CPPA (CPRA). But the scope of CalOPPA is much broader, and many businesses will not have to worry about complying with the CPPA (CPRA).

Let's take a look at how the two acts compare, and how they might apply to you.

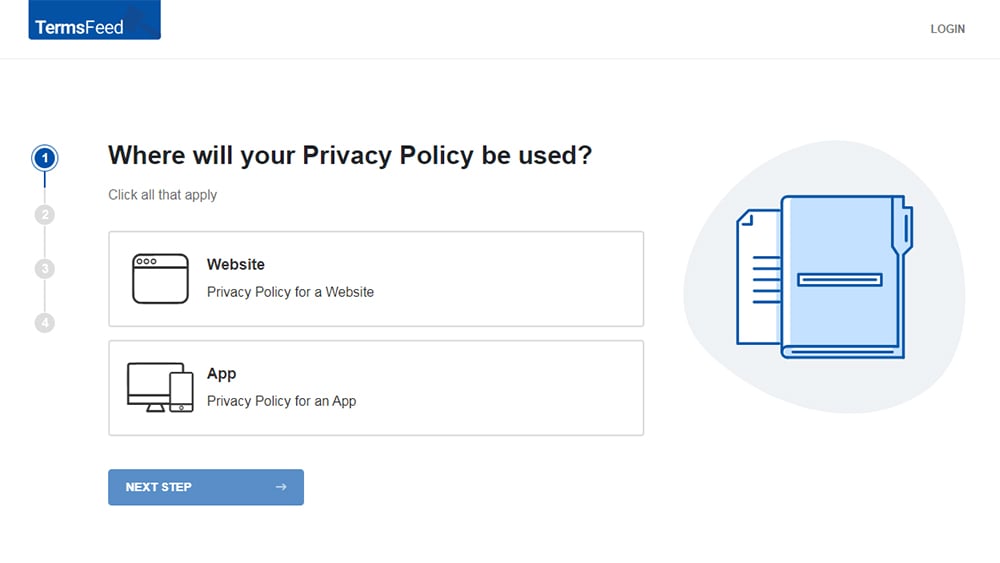

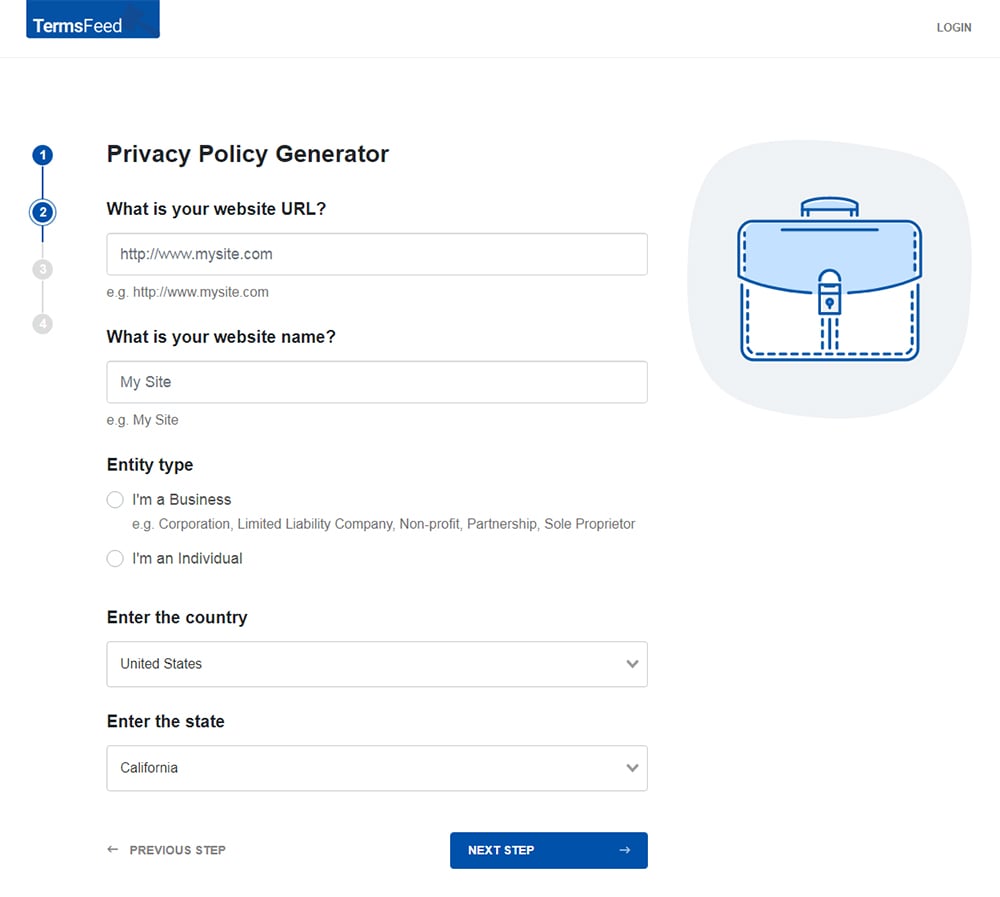

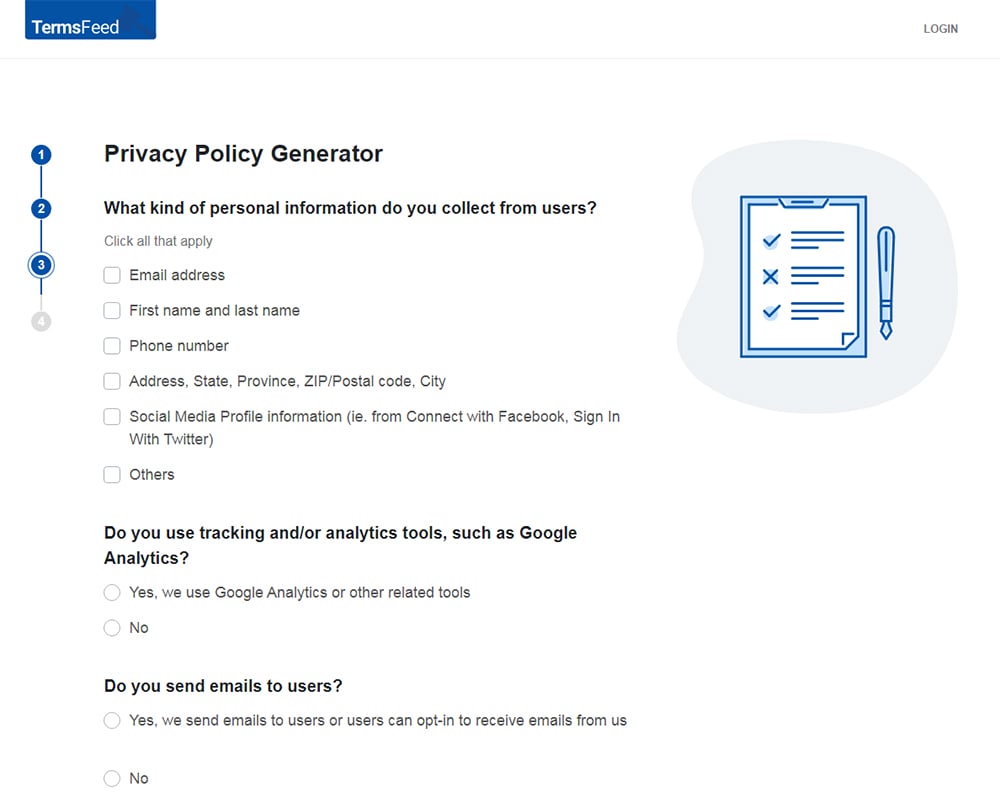

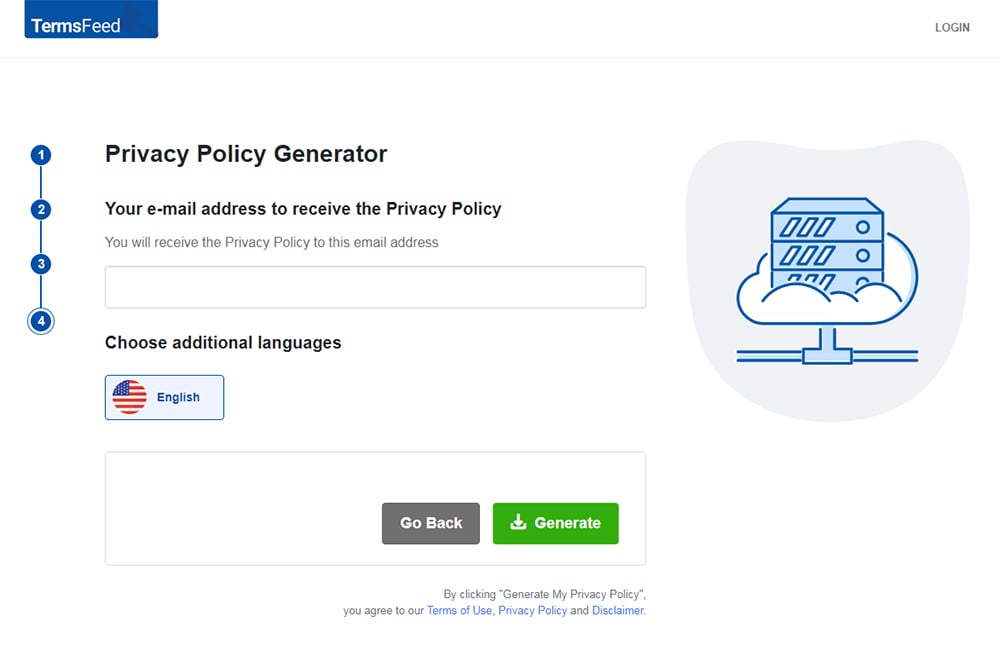

Our Privacy Policy Generator makes it easy to create a Privacy Policy for your business. Just follow these steps:

-

At Step 1, select the Website option or App option or both.

-

Answer some questions about your website or app.

-

Answer some questions about your business.

-

Enter the email address where you'd like the Privacy Policy delivered and click "Generate."

You'll be able to instantly access and download your new Privacy Policy.

- 1. Who Does Each Act Apply To?

- 1.1. Scope of CalOPPA

- 1.2. Scope of the CPPA (CPRA)

- 2. How Does Each Act Define "Personal Information"?

- 2.1. Personally Identifiable Information in CalOPPA

- 2.2. Personal Information in the CPPA (CPRA)

- 3. What Does Each Act Require?

- 3.1. Requirements Under CalOPPA

- 3.2. Requirements Under the CPPA (CPRA)

- 4. How is Each Act Enforced?

- 4.1. Penalties Under CalOPPA

- 4.2. Penalties Under the CPPA (CPRA)

- 5. Summary of Key Similarities and Differences

Who Does Each Act Apply To?

There are some similarities in terms of the scope of the two acts. They are both data protection laws, intended to protect the privacy of consumers in California. "Consumers" refers to anyone residing in California.

Both acts are addressed to commercial enterprises.

Despite these similarities, the laws are trying to achieve quite different aims among different types of businesses.

Scope of CalOPPA

The first line of CalOPPA makes it clear who the Act applies to:

"An operator of a commercial Web site or online service that collects personally identifiable information through the Internet about individual consumers residing in California who use or visit its commercial Web site or online service [...]"

There's no restriction here. The operator of a commercial website could come from Fresno or France. They could be turning over a billion dollars a year or making no money at all. All that matters is that the commercial website collects personal information about California residents. We'll look at how the Act defines personal information below.

It's important to note that CalOPPA does not apply to Internet Service Providers or other services that process personal information on behalf of a third party. It's aimed squarely at website and online service operators. However, it does apply to other types of service providers.

Those online services, by the way, include mobile apps - as was confirmed in October 2012 when the California Attorney threatened scores of non-compliant mobile app providers with fines under CalOPPA.

Scope of the CPPA (CPRA)

The CPPA (CPRA) uses the same language as CalOPPA in terms of its geographical scope. It doesn't only apply to California businesses. It applies to any business that impacts people in California.

Beyond this, the scope of the CPPA (CPRA) is very different. This is best explained by looking at how the Act defines "business."

For the purposes of the CPPA (CPRA), a "business" is any legal entity which:

- Pursues a profit,

- Operates in California,

- Determines the "purposes and means" of the processing of consumers' personal information (e.g. it decides why, and controls how), and

- Complies with one or more of the following:

- It has an annual gross revenue of more than $25 million;

- It annually buys, sells, receives or shares personal information from at least 100,000 devices, consumers or households;

- It makes at least 50 percent of its annual revenue by selling or sharing consumers' personal information.

Whenever you see the CPPA (CPRA) refer to a "business," this is what it means. The law is basically designed to hit social networks, data brokers and large corporations. Non-profits, individuals and small or medium-sized businesses that don't meet the requirements don't have to comply.

How Does Each Act Define "Personal Information"?

As we've seen, the two acts both regulate personal information - but they define "personal information" differently.

A lot has changed since CalOPPA first passed in 2004. Perhaps most significantly, the EU passed the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). EU privacy law takes an extremely broad definition of personal information. The influence of EU law on CPPA (CPRA) is clear in this respect.

Personally Identifiable Information in CalOPPA

Instead of "personal information," CalOPPA uses the term "personally identifiable information," which it defines as:

"individually identifiable information about an individual consumer collected online by the operator from that individual and maintained by the operator in an accessible form"

The following examples are given:

- Full name

- Address

- Email address

- Phone number

- Social security number

- Anything else that could allow you to contact a specific person

- Information collected by a website or online service - if stored in a "personally identifiable form" alongside other information

That last point is important. Information collected by browsers, such as cookies and IP addresses, might be personally identifiable information under CalOPPA - depending on how this information is stored. If you store someone's IP address alongside their another piece of personal information, for example their email address, the IP address constitutes personal information. Otherwise, it does not.

Personal Information in the CPPA (CPRA)

The CPPA (CPRA) defines "personal information" as:

"information that identifies, relates to, describes, is capable of being associated with, or could reasonably be linked, directly or indirectly, with a particular consumer or household."

This definition is very similar to that given under the strict privacy laws of the EU - and in fact seems even broader, given the inclusion of the word "household."

The CPPA (CPRA) gives a lot of examples. We won't look at them all. But significantly, in addition to those given under CalOPPA, the CPPA (CPRA) includes:

"Internet or other electronic network activity information, including, but not limited to, browsing history, search history, and information regarding a consumer's interaction with an Internet Web site, application, or advertisement."

The CPPA (CPRA) also makes reference to IP addresses and location data, which constitute personal information in their own right.

There are big implications here - information that websites collect as a matter of routine, for example in their web server log files, now unambiguously qualifies as personal information - and must be treated as such.

What Does Each Act Require?

CalOPPA was the first US law that required website operators to display a Privacy Policy on their websites. The CPPA (CPRA) takes these basic requirements a lot further, and also grants Californians some new privacy rights.

Requirements Under CalOPPA

CalOPPA requires that websites display a Privacy Policy which discloses basic information about the website's privacy practices.

Firstly, the Policy must disclose:

- The categories of personal information collected. For an ecommerce website, for example, this will include a person's name, email address, shipping address, payment details, etc.

- The categories of third-parties that might receive the information. You could list "a payment processor" or "a mail carrier" without specifically naming these companies.

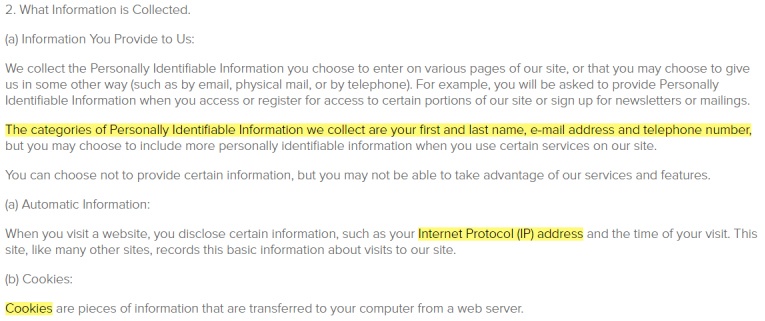

Here's an example from Agency Central:

You'll also need to include Information about procedures and processes:

- A description of any process you might have in place that allows consumers to review and request changes to the information held on them. Note that CalOPPA doesn't mandate this process - it only requires that you describe any such process you might have in place.

- A description of the process that you use to inform consumers of any changes to the Privacy Policy.

- The date from which the Privacy Policy takes effect.

Here's an example from October Club:

CalOPPA was amended in 2014 so that Privacy Policies now also have to include technical information such as:

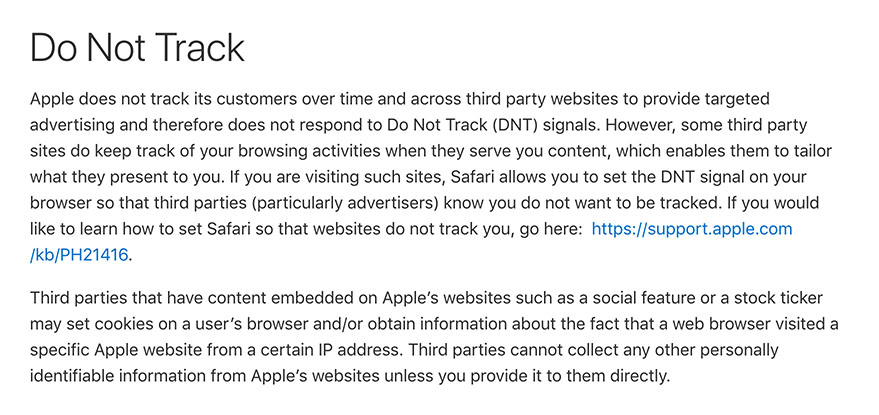

- A disclosure of whether your website honors "Do Not Track" (DNT) signals.

This is a browser setting which requests that website does not apply tracking technology to the visitor. Note that CalOPPA doesn't specify how you should treat such signals, only that you disclose how these are treated. You can also link to a resource such as a browser extension that will provide this facility.

- Where your website integrates third-party software or resources, whether these will result in the consumer's personal information being shared outside of your website.

Here's an example from Apple:

The Privacy Policy must be "conspicuously posted." This means that your website's homepage should have a link to the policy containing the word "privacy" and written in text that's easily noticeable:

![]()

Requirements Under the CPPA (CPRA)

Whilst fewer businesses are required to comply with the CPPA (CPRA) than with CalOPPA, compliance takes a lot more work.

If you're familiar with the EU's GDPR, you'll know about the rights it gives EU residents in relation to their personal information. The CPPA (CPRA) provides Californians with a similar set of rights, including the following. It's the job of businesses to help them access these rights:

- The right to know - businesses must disclose to a consumer the specific pieces of personal data they collect, sell or disclose about them.

- The right to say no - businesses must cease to sell a consumer's information on request.

- The right to deletion - under certain conditions, businesses must a consumer's certain information.

- The right to non-discrimination - businesses may not discriminate against consumers who have exercised these rights.

- The right to limit the use of sensitive personal information

- The right to opt out of automated decision-making.

The CPPA (CPRA) also requires that children opt in to any sale of their personal data.

Businesses that fall within the CCPA/CPRA's scope must amend their Privacy Policies to include certain information, and must update this information once per year.

The Privacy Policy must include a description of some of the rights under the CPPA (CPRA):

- The right to know what personal information the business holds on a consumer or sells about them, together with details on how consumers can access this right.

- The right to non-discrimination.

The CPPA (CPRA) specifies three lists that need to be included in the Privacy Policy:

- A list of the categories of consumers' personal information the business has collected in the preceding year;

- A list of the categories of consumers' personal information the business has sold in preceding year - or, if it hasn't sold any personal information, a declaration of this.

- A list of the categories of consumers' personal information the business has shared for business purposes in preceding year - or, if it hasn't sold any personal information, a declaration of this.

The CPPA (CPRA) also requires the business to provide a conspicuous link reading "Do Not Sell My Personal Information," which leads to a page where the consumer can notify the business that they do not wish them to sell their personal information. A toll-free phone number must also be provided by some businesses.

The CPPA (CPRA) has Notice requirements that you'll need to become familiar with as well, which we address in detail in our article: CCPA Notices.

How is Each Act Enforced?

Violating either act can lead to fines and could be disastrous for any business. However, there are differences concerning who can bring an action, and what the maximum penalty is under each act.

Penalties Under CalOPPA

The penalty for non-compliance with CalOPPA, for example by failing to display a Privacy Policy, is a maximum $2,500 per violation, pursuant to Section 17206 of the Business and Professions Code.

That doesn't sound too bad - until you consider what counts as a "violation." Each time a California resident visits your non-compliant website or downloads your non-compliant app could count as an individual violation.

For example, the California Attorney General sued Delta Airlines for not having a Privacy Policy in its mobile app. As it happens, Delta escaped a fine, but the total amount would have been based on the number of users of the app. Even with just a few hundred users, you can imagine the huge sums that could result from failing to display a CalOPPA-compliant Privacy Policy.

There's no way for an individual to bring a private case based on a CalOPPA violation - the law is enforced by the California Attorney General.

Penalties Under the CPPA (CPRA)

The enforcement of the CCPA is a little more complicated. There are three ways that a company might end up being fined under the CCPA.

Firstly, like CalOPPA, the Attorney General can issue penalties of up to $2,500 per Section 17206 of the Business and Professions Code. Twenty percent of the total penalty will be paid into a Consumer Privacy Fund, designed to help the Attorney General recover the costs of legal action brought under the Act.

Secondly, the CPPA (CPRA) also states that a business that intentionally violates the Act may be fined up to $7,500 for each violation.

Thirdly, private claims can be brought by consumers. This is only possible in the event that a business covered by the CPPA (CPRA) allows "unauthorized access and exfiltration, theft, or disclosure" of a consumer's data, owing to a failure to maintain "reasonable security procedures."

Each consumer can recover between $100 and $750 per incident, or actual damages - whichever is higher. "Actual damages" means any amount of money or property that the consumer actually lost as a result of the security incident.

Summary of Key Similarities and Differences

CalOPPA and the CPPA (CPRA) are among the most comprehensive privacy laws in the United States. Together, the acts provide a powerful set of protections for California consumers' privacy.

They share some similarities and differences in terms of scope:

- Both CalOPPA and the CPPA (CPRA) are about privacy and data protection.

- Both acts are addressed to commercial enterprises.

- Both acts are intended to apply to anyone doing business in California - whether based there or not.

- Both acts are designed to protect consumers. Where the acts refer to "consumers," this means people residing in California.

- CalOPPA is addressed to anyone running a commercial website.

- The CPPA (CPRA) is addressed to big businesses with revenues of at least $250 million, and data brokers whose primary business is in sharing and selling consumers' personal information.

They have slightly different definitions of personal information:

- Both acts include what might be "obvious" personal information such as names, addresses and contact details.

- The CPPA (CPRA) has a much broader definition including browser data and IP address. It also includes any information that could be used to identify a "household."

The acts have different requirements:

- CalOPPA requires websites and apps to identify:

- The categories of personal information the website collects;

- The categories of third parties that might receive the information;

- Information about the Policy itself, including how changes to the Policy might be communicated;

- How the website treats DNT requests and third-party cookies.

- CPPA (CPRA) requires businesses to disclose:

- Consumer rights under the CPPA (CPRA) and how they might be exercised;

- The categories of personal information the business has collected, sold or shared in the past 12 months;

- How the consumer can object to the selling of their data, via a "Do Not Sell My Personal Information" link.

There are also different penalties for each act.

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.