Browsewrap and clickwrap are different methods used for binding users to a set of terms. Clickwrap obtains active, overt consent for something, while browsewrap obtains implied consent that isn't always legally binding.

It's important for business owners to understand the difference between browsewrap and clickwrap and what makes a legal agreement enforceable.

This article will break down the differences between browsewrap and clickwrap and how you should best use them to your benefit to get users to agree to your terms.

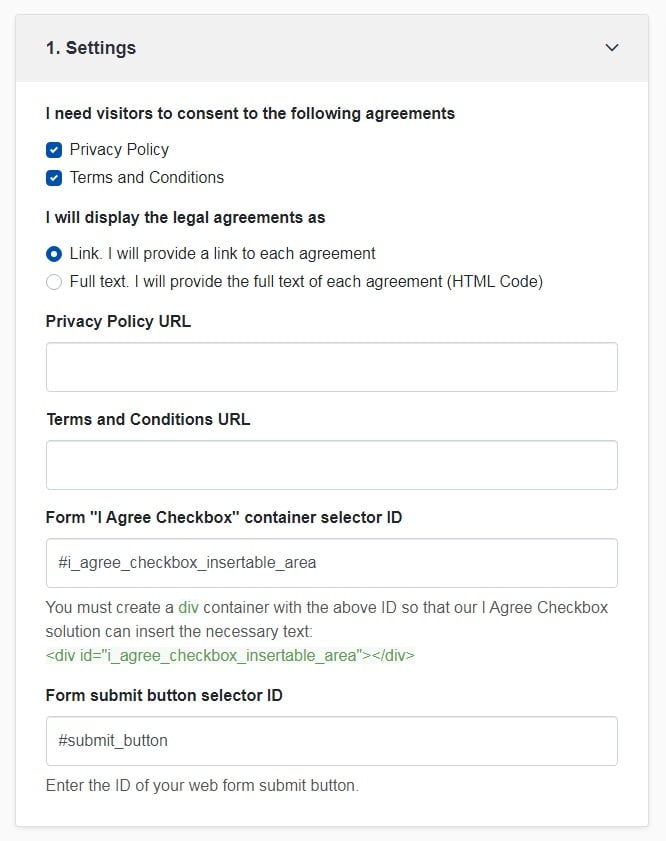

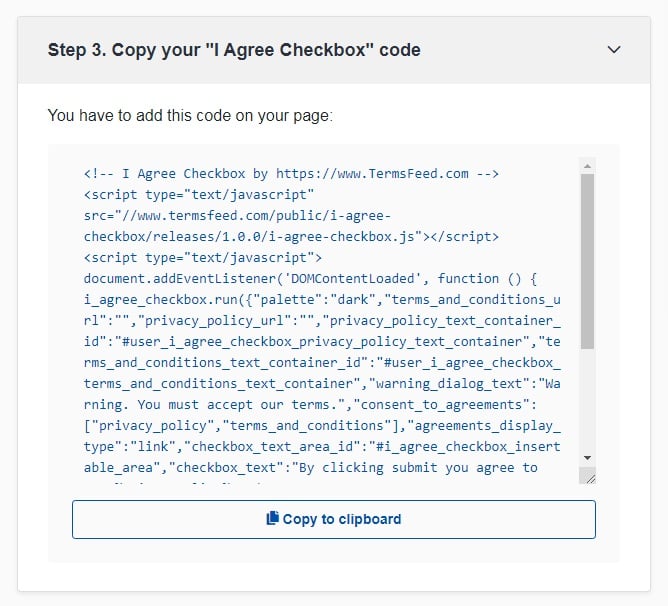

"I Agree" Checkbox by TermsFeed tool can help you enforce your legal agreements in 3 easy steps.

-

Step 1. Adjust the settings in order to display your legal agreements properly.

-

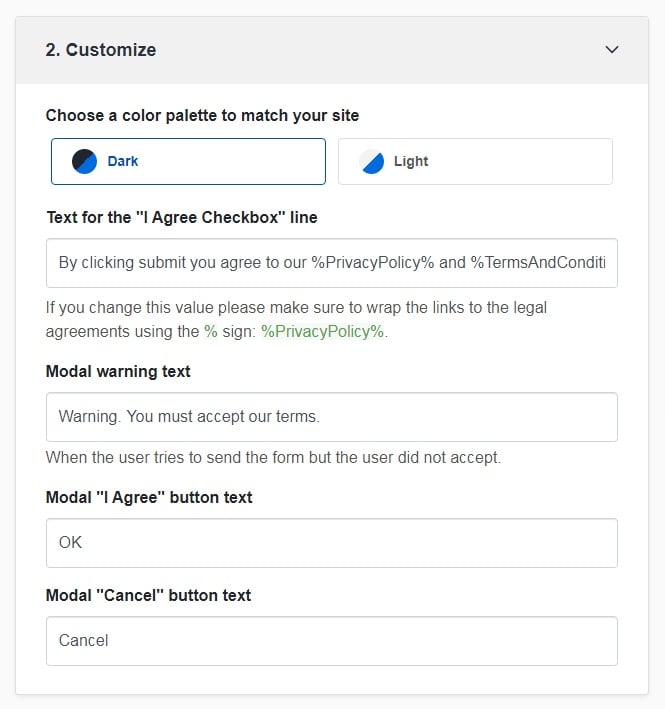

Step 2. Customize the style to match your brand design.

-

You're done! Just copy the generated code from Step 3 and copy-paste it on your website.

- 1. What are Browsewrap and Clickwrap?

- 1.1. More About Browsewrap

- 1.2. More About Clickwrap

- 2. Key Differences Between Browsewrap and Clickwrap

- 3. How to Enforce a Legal Agreement

- 4. Providing Notice

- 4.1. Short Overview of Providing Notice Cases

- 4.1.1. Forrest v. Verizon

- 4.1.2. DeJohn v. The .TV Corporation

- 4.1.3. Motise v. America Online

- 4.1.4. Specht v. Netscape

- 4.1.5. Hubbert v. Dell

- 4.1.6. Cairo v. CrossMedia Services

- 4.1.7. Zaltz v. Jdate

- 4.2. Why You Shouldn't Use Browsewrap

- 5. Obtaining Consent

- 5.1. Short Overview of Obtaining Consent Cases

- 5.1.1. Ticketmaster v. Tickets.com

- 5.1.2. I.Lan Systems v. Netscout Service Level

- 5.1.3. Scherillo v. Dun & Bradstreet

- 6. Fairness

- 6.1. Short Overview of Fairness Cases

- 6.1.1. Caspi v. Microsoft

- 6.1.2. Comb v. PayPal

- 6.2. International Views

- 7. Best Practices

What are Browsewrap and Clickwrap?

These are two different methods for getting users to agree to your website legal agreements, such as a Privacy Policy, Terms and Conditions (also known as Terms of Use or Terms of Service), EULA, Cookies Policy or any other agreement.

Most legal agreements are often presented to users through either a clickwrap agreement or a browsewrap agreement.

The wrap portion of both words is a derivation of the shrink-wrap agreement, where customers would find a contract within the good that had been sealed or shrink-wrapped within the good's packaging.

The shrink-wrap agreement would often state that by opening the package, the purchaser agrees to a set of terms.

While browsewrap really only exists in the digital space, the method of use is similar to shrink-wrap in physical goods.

More About Browsewrap

Browsewrap refers to a method of deeming acceptance of terms based simply on the fact that someone is using something - a website, a mobile app, a piece of software, a service.

A link is located somewhere on a website that takes a user to the Terms agreement or Privacy Policy page.

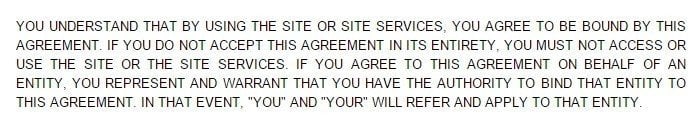

In the agreement, there's usually one sentence or clause that states something along the lines of, "By accessing or using the Service you agree to be bound by these Terms."

No overt action to acknowledge acceptance of terms is required, and nothing is done to prove that the user was even aware that these terms existed.

Here's an example of a statement that shows browsewrap:

This discreet fine print requirement to be bound by an agreement you maybe never knew existed typically wouldn't pose a problem. However, it can be a huge issue if any disputes arise between the website and a user who may be in alleged violation of the Terms of Service agreement. This is because the user is supposed to be bound bythe terms and yet may have not even known about them.

For an agreement to be legally binding, both parties must be aware of the agreement.

Businesses could run into trouble here by having a difficult time proving that there was an actual consent over their presented Terms of Service and Privacy Policy.

Because of this ambiguity and lack of meeting of the minds under the browsewrap method, clickwrap should always be used.

More About Clickwrap

Clickwrap gives notice to a user that there are terms, conditions are rules that go along with the website or mobile app, and requires overt consent, such as by having a user check or toggle an "I Agree" or "I Consent" checkbox or button before having access to a website. At minimum, it will be clear that by proceeding onward into the website the user is accepting these terms.

Start generating the necessary legal agreements for your website or app in minutes with TermsFeed.

We also offer different solutions and tools for your website or app:

- Privacy Consent (Cookie Consent). A cookie consent solution to comply with CCPA/CPRA, GDPR, ePrivacy Directive.

- CCPA/CPRA Opt-Out. A free CCPA/CPRA opt-out solution to allow visitors to opt-out from personalized ads and comply with CCPA/CPRA.

- "I Agree" Checkbox. A free solution to enforce your legal agreements.

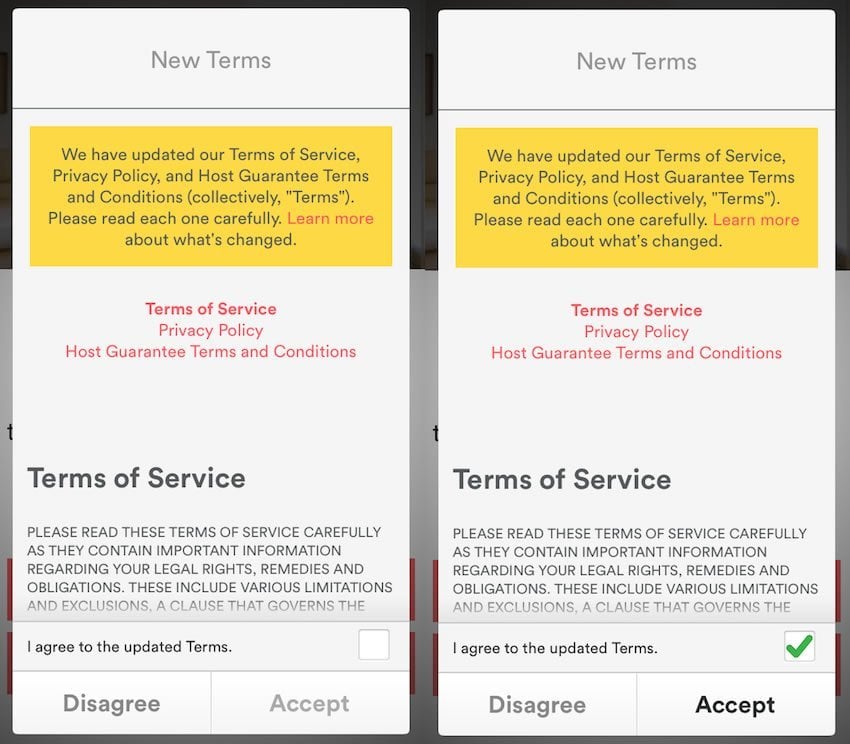

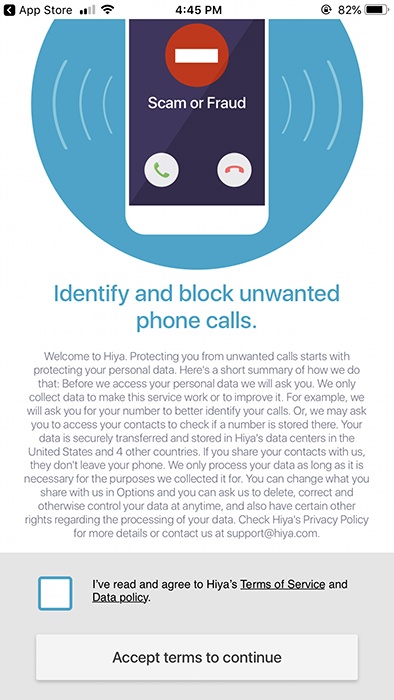

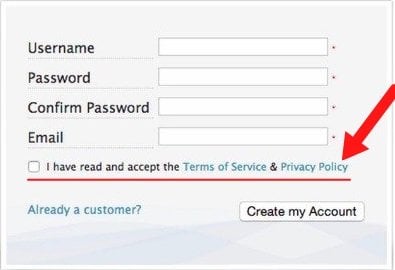

Here's an example of how you can request a user click to agree to Terms of Service before signing up or logging in. This ensures that everyone who uses the website for its services has actively consented to agree and has access to these terms:

By requiring active clicking to show consent and acceptance of Terms and Conditions or a Privacy Policy, a website or mobile app can better enforce its terms and rules and be protected against abuses by users.

Likewise, users will have a better idea of what exactly they are signing up for and committing to do or not do.

Key Differences Between Browsewrap and Clickwrap

The key difference is that clickwrap requires an actual action showing consent, while browsewrap assumes consent is given almost automatically.

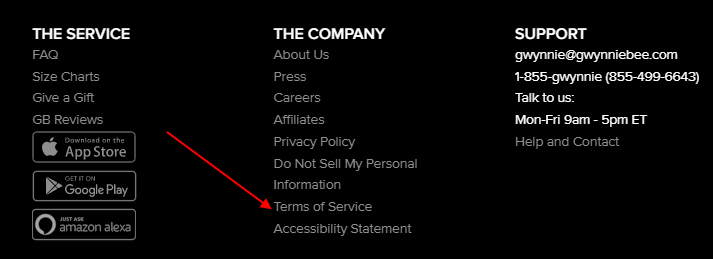

Browsewrap involves two components: A hyperlink at the bottom of the website that redirects the user to the legal page, be it a Privacy Policy or a Terms and Conditions agreement, and the agreement saying something like we showed above, that the user is bound by the terms by simply using the site.

Note that clickwrap also uses this footer linking, but in conjunction with a checkbox or some sort of overt method of obtaining consent from users to actually be bound by the terms rather than simply using the site.

A clickwrap agreement will go above and beyond simply linking a legal agreement to a website/mobile app. Instead, clickwrap will require a user to take some action to give consent such as clicking the commonly-seen "I agree" checkbox in order to create an account, order a product, continue towards a new section of the website etc.

These methods are exactly what browsewrap is not: the legal agreements are given increased notice in front of a user to maximize the chances that the agreements were read, understood and agreed to.

Here is a classic, standard example of clickwrap, where a user must check a box next to a clear statement that says, "I agree to the terms of service."

Most agreements, at least on websites, will typically be linked to in the website's footer, like so:

Most agreements will include text that says something similar to the following:

Welcome to the Our Website ('Site'). Please review the following basic terms that govern your use of and purchase of products from our Site. Please note that your use of our Site constitutes your agreement to follow and be bound by those terms the 'Agreement').

However, if the agreement is later disputed, it matters how you presented your agreements, its terms and its rules.

All businesses, especially online businesses, should take precautions to ensure that users have been properly given notice of any terms, rules, agreements or policies that they need to agree to, and that agreement has been clearly obtained.

In other words, certain factors may affect the enforceability of an agreement later on, such as:

- Whether the agreement was presented in a clear and unambiguous manner

- If the agreement was reasonably consented (agreed) to

No business ever wants to take a dispute to court only to find that its legal agreement is not enforceable. Thankfully, much of this is in your control with how you display and get consent to your agreements.

How to Enforce a Legal Agreement

When it comes to enforcing a legal agreement, clickwrap takes the prize as being the compliant, effective method. It shows clear notice and agreement which can be enforceable in a court of law.

Specifically, the list of what makes an agreement enforceable can be boiled down to:

- Whether the user was provided notice

- Whether the user gave consent

- Whether enforcing the agreement is fair

Providing Notice

Whether the user was properly on notice of the agreement is an important benchmark for the validity of a browsewrap or clickwrap agreement.

For agreements to be enforceable, all contracting parties must knowingly agree to all of the different aspects of the contract. Both parties must be aware or have had reasonable opportunity to become aware of the existence of the terms of the agreement.

How this concept of notice applies to the two kinds of agreements can be distinct.

With clickwrap agreements, establishing notice isn't typically a problem. When the user accesses a website or mobile application that has a clickwrap agreement, in most cases the user will be asked if they agree to that agreement.

This is done before the user may access the content or the service of that website or mobile app. It provides the user with notice of the contract they are entering.

Here's a great example of how to present Terms agreements or updates to one via a mobile app:

Short Overview of Providing Notice Cases

Here are a few cases that have been litigated that deal with how notice is provided, and when it's legally adequate.

Forrest v. Verizon

An example of the effective use of a clickwrap agreement used to provide notice is shown in the "Forrest v. Verizon" case. In this case, a dispute arose between a customer and Verizon over a small clause detailed in Verizon's Terms of Service.

The customer was upset over that particular clause and claimed that Verizon had not provided them with notice of this term. The customer had assented to a clickwrap agreement that was within a scroll box.

Across the top of the clickwrap agreement were the words:

PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING AGREEMENT CAREFULLY.

The user was required to click that they agreed to Verizon's Terms of Service before they could continue with the completion of the transaction.

It's important to note that Verizon's Terms of Service scroll box was:

- Small

- Approximately thirteen pages long

- Difficult to read

The particular clause that was disputed in this court case was towards the end of the agreement as well.

In spite of those factors, the appellate court disagreed with the customer and determined that they were provided with ample notice.

By comparing the scroll wheel to a standard multi-page contract, the court cited the basic principle of contracts that when someone signs a contract they had an opportunity to read, they should be bound to the agreement, regardless of whether they actually read the contract.

DeJohn v. The .TV Corporation

In similar fashion to "Forrest v. Verizon," courts have continued to reinforce these contractual notions found in clickwrap agreements.

In "DeJohn v. The .TV Corporation," a court held that a clickwrap agreement was valid despite the terms of the contract being fairly inconspicuous.

The court echoed the notion that as long as the parties to the agreement had an opportunity to review the terms and click that they consent, they had been given enough notice.

Motise v. America Online

In "Motise v. America Online," the reviewing court enforced aspects of a terms agreement against a customer of AOL.

The customer's stepson, who had never seen or agreed to the terms, was found to be a sub-licensee of the customer and was thereby bound to the same terms as the customer.

In light of these cases, lengthy legal clickwrap agreements that require user confirmation are enforceable, as long as a responsible user has consented.

Specht v. Netscape

Providing notice through a browsewrap agreement is different than clickwrap.

Instead of requiring the user to manually agree to the agreement, the user implicitly agrees by mere use of the website or the mobile app.

The user never actually takes an affirmative action besides the use of the site or the mobile app. This can lead to some problematic results.

In "Specht v. Netscape," an appellate court reviewed a browsewrap agreement on the Netscape website.

In this case, the user was presented with a download link for software and could only review the Terms of Service for that download by scrolling to the next page. The user had downloaded the software without having seen the agreement and then was sued for federal violations arising out of use of the software.

The court explained that one essential element to contract formation is the mutual manifestation of assent noting that:

[...] a consumer's clicking on a download button does not communicate assent to contractual terms if the offer did not make clear to the consumer that clicking on the download button would signify assent to those terms.

Because the user was neither made aware nor required to be aware of certain terms before using the software, the browsewrap agreement was held to be unenforceable against the user.

Hubbert v. Dell

However, other browsewrap agreements have been enforceable as long as certain measures were taken.

In "Hubbert v. Dell," customers using Dell's website were shown the words "All sales are subject to Dell's Terms and Conditions of Sale" recurrently and were provided with an obvious hyperlink to Dell's Terms and Conditions agreement.

When a dispute arose over whether a customer was provided notice of the terms, the reviewing court made clear that repeated exposure of this nature would put a reasonable person on notice, as long as it was presented directly and unambiguously.

Browsewrap agreements have the inherent protection that repeated use of or interaction with a website indicates a certain level of awareness of their existence, and therefore notice.

Cairo v. CrossMedia Services

In "Cairo v. CrossMedia Services," a user had used the Cross Media Services website on numerous occasions.

When a dispute arose, the court found that Cairo's repeated use of CrossMedia Services formed the evidential basis that Cairo had a working basis and knowledge of the website, which included the Terms of Service agreement.

If you're using a browsewrap agreement, the more a user has had the opportunity to see and read your Terms and Conditions agreement, the more likely a court will enforce the Terms and Conditions agreement against that user.

Zaltz v. Jdate

There's some legal indication that a hybrid of a clickwrap and browsewrap agreement can be used to further provide enforceability to an agreement.

In "Zaltz v. Jdate," Zaltz sued the online dating website JDate for harassment related to billing in New York.

JDate moved to have the case transferred to California as it was agreed to in the license agreement displayed on JDates website. Zaltz had noted that she "didn't believe that she agreed to such a clause."

However, the court responded that:

[...] the fact that the plaintiff cannot remember the terms that she was presented with when she joined, or that she simply does not believe that she agreed to the terms, does not negate the uncontroverted and overwhelming evidence demonstrating that plaintiff could not have become a member of JDate.com without first agreeing to the websites Terms of Service.

Because JDate had a statement that in order to join the site a user would have to click a specific box to accept the Terms of Service confirming that they did agree, JDate was providing both the information within the Terms of Service and also requiring some action that would confirm a user's consent.

This combination of the browsewrap and clickwrap elements allowed for JDate to enforce the Terms and Conditions agreement against Zaltz.

When considering which agreement would better protect your website or your mobile app, remember that the real objective is to clearly and reasonably provide notice to the user.

That notice could come in the form of a pop-up window with obviously labeled hyperlinks or several bold clear disclaimers across the top of the page, as long as it puts the user on notice.

Why You Shouldn't Use Browsewrap

One of the main downfalls of browsewrap is that it really does little to keep your users in the loop of the policies and terms of your web site or mobile app. Also, courts don't like it.

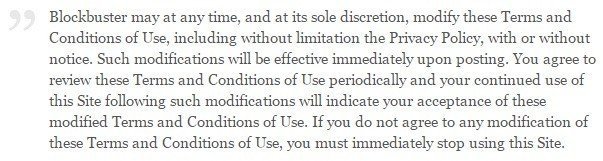

Consider the case of Harris v. Blockbuster, Inc. where Blockbuster's user agreement included the following language:

Blockbuster may at any time, and at its sole discretion, modify these Terms and Conditions of Use, including without limitation the Privacy Policy, with or without notice. Such modifications will be effective immediately upon posting. You agree to review these Terms and Conditions of Use periodically and your continued use of this Site following such modifications will indicate your acceptance of these modified Terms and Conditions of Use. If you do not agree to any modification these Terms and Conditions of Use, you must immediately stop using the Site.

The court found that this language made for portions of the agreement to be "illusory" because they really could be changed at any time and with no actual notice and no actual acceptance or agreement to the change.

This case showed that to really lock a user into the Terms of Service or Privacy Policy you dictate for your web site or mobile app, you absolutely need to give actual notice that you have terms, rules and policies and get an actual agreement to them.

If you change the terms of your Terms of Service agreement or your Privacy Policy agreement, you need to give notice to your users that the agreements have changed and get a new consent to your new terms of these legal agreements.

Obtaining Consent

For an agreement - clickwrap or browsewrap - to be enforceable, the agreement must have been consented to by both parties, and what is sometimes referred to as a meeting of the minds.

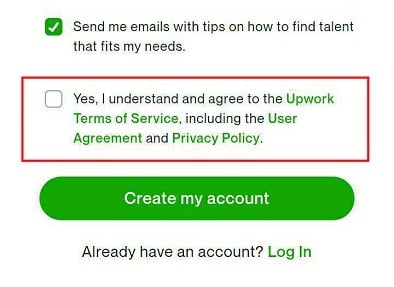

Whether you have a website, mobile app, or desktop app/software program, always use the clickwrap method to obtain consent and agreement for your Terms of Service, Privacy Policy, Cookies Policy, or any other legal document that you wish to be able to enforce.

This method will ensure that your users are aware that you have such documents and will give them easy access to the documents. It will also ensure that your users will actually be in agreement with the documents should a dispute or issue ever arise.

Consent can be broken into two categories: Express and implied.

Express consent is clearly and unambiguously stated, and may be obtained rather easily through verbal or non-verbal methods.

Implied consent is unspoken and is inferred from the person's actions or non-actions. Implied consent requires more to prove when enforcing an agreement.

Courts are less likely to bind a user to an agreement they consented to in an implied way.

Why is this important for website owners or mobile app owners when considering the enforceability of their agreements? Consent is a low bar to meet, but an essential element of contract formation.

To be enforceable, implied or express consent must be given by the user.

One problem with browsewrap agreements is the way they obtain consent.

Users don't typically purposefully consent to browsewrap agreements. Rather, browsewrap agreements are written in a manner that gathers consent by the user's action, such as browsing a website. Therefore, the consent is implied and might be harder to prove when seeking to enforce the agreement.

Short Overview of Obtaining Consent Cases

Here are overviews of a few cases that have been litigated around the topic of what is valid consent.

Ticketmaster v. Tickets.com

In "Ticketmaster v. Tickets.com," Tickets.com had been taking information directly from Ticketmaster's website, making minimal formatting changes, and then placing it directly on its own website.

Ticketmaster sued to enforce the clause in a Terms of Use agreement that prohibited using information gathered from their website for commercial purposes.

Ticketmaster's Terms of Use agreement of was presented in a browsewrap manner with tiny print that hyperlinked to the agreement:

The reviewing court found that the browsewrap agreement wasn't enforceable because it didn't unequivocally prove that Tickets.com had given its consent.

Thus, browsewrap agreements can make it difficult to provide evidence that the user agreed to the agreements, its terms, and its rules.

Clickwrap agreements, by their very nature, obtain clear consent. Because clickwrap requires the user to manually click "I agree" or something similar before continuing, it's much easier to demonstrate that the user did in fact agree:

However, courts are less comfortable if the terms are unclear on the acknowledgement of consent.

I.Lan Systems v. Netscout Service Level

In "I.Lan Systems v. Netscout Service Level," a dispute arose whether I.Lan was subject to the terms of a clickwrap agreement.

I.Lan had purchased software from Netscout. Netscout had not used clickwrap for its terms agreement until after the sale to I.Lan. However, the agreement was prominently placed within the software.

I.Lan had been shown the agreement and was required to check a box stating "I agree."

The reviewing court determined that being shown the terms within the software and requiring manual consent before continuing was enough to evidence consent.

However, consent is a nebulous term and for enforcement, all that's really required is evidence that consent occurred. Disputes that arise out of supposed unfairness need concrete proof of the disparity. Otherwise, the court will often find consent.

Scherillo v. Dun & Bradstreet

For example, in "Scherillo v. Dun & Bradstreet," a reviewing court enforced a clickwrap agreement against Scherillo.

Scherillo argued that despite the fact that he checked a "Yes" box in relation to the legal agreement, he had not meant to do so. Therefore, he felt as if he had not consented.

However, the court disagreed, stating that the terms agreement was reasonably communicated, and based on the evidence a reasonable person would not have clicked "yes" to consent unless they actually consented.

Considering the values and weights of both the clickwrap and browsewrap agreement regarding consent, clearly clickwrap provides better enforceability:

Although browsewrap agreements can implicitly gain consent, the benefit of clickwrap protections outweighs any slight difficulty passed on to the user.

Fairness

A third factor when weighing the enforceability of clickwrap agreements and browsewrap agreements is whether the enforcement of the agreement would be fair. While this sounds quite vague, there are two main elements of fairness at play: Whether enforcement of it would be unconscionable, and whether the agreement was formed with inequality of bargaining power.

Let's look at each.

First, whether enforcement of the agreement would be unconscionable.

An unconscionable contract is an agreement that no reasonably informed person would otherwise agree to.

Factors that contribute in the consideration of unconscionability are things such as age and mental capacity. Although for a user to prove that an agreement was unconscionable is a difficult task.

Second, whether the agreement the agreement was formed with an inequality of bargaining power. This is where one party to an agreement has better substitute options than the other party.

If a court finds this inequality to be so great that it is unfair, they'll refuse to enforce the agreement. This is a high bar to meet. For a user to prove that an agreement is unfair is a difficult task.

However, similar disparities between clickwrap and browsewrap agreements present themselves here, as they do in other facets of enforceability consideration.

Short Overview of Fairness Cases

Here are some cases that have been litigated over what counts as "fair" for these purposes.

Caspi v. Microsoft

In "Caspi v. Microsoft," Caspi had agreed to the Microsoft clickwrap agreement, which had contained a choice of forums clause that stated all disputes would be brought in a court in King County, Washington.

Microsoft's principal place of business is in King County.

Later when a dispute arose, Caspi claimed that the entire clickwrap shouldn't be enforced because it was unconscionable. However, the reviewing court disagreed because there was no fraud, no unequal bargaining power, and Caspi had affirmatively agreed to the terms of Microsoft's agreement.

In this instance, Caspi had agreed to fairly reasonable terms and had done so explicitly.

Comb v. PayPal

In contrast, to this in "Comb v. PayPal," the court refused to enforce a browsewrap agreement for fairness factors.

PayPal's Terms of Service were provided to the user but did not require explicit consent before the use of any services from PayPal. The terms once printed were over twenty pages and ambiguous.

Based on these factors as well as other attenuating circumstances, the reviewing court found that certain clauses were unconscionable and unenforceable.

Yet again, because of browsewrap agreement's implicit consent and notice, clickwrap provides more protection of enforceability than browsewrap agreements do.

International Views

It's important to note that these cases listed above are only directly applicable to U.S. law. However, they're still important for business owners outside the United States. The laws of the U.S. do shape international policies as well and will set the foundation for other countries decision.

Here's an example from a court decision.

In the Canadian case of "Century 21 v. Rogers Communications," Century 21 sued Canadian real estate search engine Zoocasa for infringing the agreement on Century 21's website, including breach of copyright and breach of contract.

Zoocasa's search engine was allegedly using Century 21's website information for Zoocasa's monetary benefit which was against the legal agreement of Century 21's website.

Canadian law on contracts "requires that the offer and its terms be brought to the attention of the user, be available for review and be in some manner accepted by the user."

The reviewing court decided that Zoocasa had notice of Century 21's browsewrap agreement and Zoocasa accepted it by their continued use of the website listings.

Therefore, Canada is mirroring the United States in forming its case law on browsewrap and clickwrap agreements to remain relevant in a digital age of mass commerce.

Interestingly enough, the court in "Century 21 v. Rogers" cited an overwhelming amount of U.S. cases covering notions of contract law, browsewrap, clickwrap, notice, consent, and fairness.

This shows that other countries are looking towards U.S. courts decisions to inform themselves on where they might go as well.

Best Practices

In light of these court decisions, website owners or mobile app developers should take several precautions when deciding which implementation technique of the legal agreements they should use.

If your business is looking to use a clickwrap agreement, consider the following:

-

Clearly display the legal agreement in a clear and noticeable location on the website or within the mobile app.

- Make the method of acceptance or denial unambiguous.

- Clearly indicate that by accepting the agreement, the user is on notice of the legal contract that they explicitly consented to.

If users can register an account on your website or mobile app, give proper notice of the legal agreements that they must agree to before they can create an account with you.

If you're placing a checkbox before users can continue with a certain action such as creating an account," make sure that if the checkbox is unchecked, users can't create an account:

Provide a notice with links to your legal agreements any time a user either creates an account or purchases a good or a service.

When displaying the notice, require that the user takes some form of action to consent to the agreement if they choose. This allows demonstrable evidence that the user had clear notice and affirmatively accepted to be bound to the terms.

Finally, if any changes occur with an agreement, even small ones, notify each existing user of the changes you're making to that agreement.

Here's how Google provided notice of upcoming updates to its Terms of Service:

![]()

We do not recommend using browsewrap agreements.

When it comes to getting agreement to your legal agreements, for placing cookies, sending marketing emails and other things you need consent to do, clickwrap is by far the way to go. It's the modern approach to consent, and it's likely going to be the only acceptable way to get consent in the future of privacy law:

Always use a checkbox and a clearly labeled button when possible to get the best level of compliant consent.

Comprehensive compliance starts with a Privacy Policy.

Comply with the law with our agreements, policies, and consent banners. Everything is included.